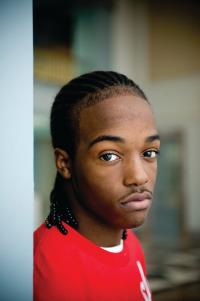

Brandon Saunders has trouble believing there are places like New Trier High School — a public school with an ivy-walled, university-like campus, with gyms for almost every sport, a multi-room college counseling center, and bright-eyed teachers planning their lessons in cubicle-like offices as up-to-date as any in corporate America.

"It's immaculate," he said after seeing New Trier's campus. "I was blown away."

Amanda Cohen has trouble believing there are schools where kids have to share textbooks, where parents are asked to supply toilet paper, and where no one comes to fix a bathroom without a door.

"People are telling me these stories and I'm thinking, how can you study in this environment?" she said. "How can you feel safe?"

Some people would say that Brandon and Amanda are from two completely different worlds. But they really live in the same world: a place called Chicagoland, a single metropolitan area divided by race, class and income.

She lives in Winnetka, a mostly-white suburb of Chicago. He lives a short train ride away, on Chicago's mostly-black South Side. Brandon's school spends about $11,000 per student per year, while Amanda's school spends more than $17,000. It's segregation in all but name.

They aren't going to take it any more. Brandon and Amanda are both part of a newly-formed group called the Illinois Council of Students, a coalition of kids from some of the Chicago area's richest and poorest districts, which is mounting a statewide effort to end school inequity in their state once and for all.

"We want to talk to the people who make the decisions," Brandon said. "I want to say 'look me in the eye and tell me I can't have new books and the resources these other schools have.'"

'Totally Separate, Totally Unequal'

It all started when Brandon skipped the first day of his senior year at Chicago's Morgan Park High School, where hallways swelter without air conditioning and new teachers seem to come and go as if through a revolving door.

Instead of heading to Morgan Park, he boarded a bus bound for Winnetka, a picturebook suburb of manicured lawns and two-story houses on the shores of Lake Michigan. Beneath its everyburb mystique, Winnetka is, per household, one of the richest zip codes in the nation.

Brandon came here to register as a student at the town's New Trier High School — a campus with tennis courts, an art gallery, and a theater that would make most university drama departments proud.

He didn't come to New Trier alone. Brandon was one of more than 1,000 students from Chicago Public Schools — almost all of them African American — who made the trip to Winnetka and New Trier.

It was a symbolic move. The school could not, by law, admit them, and technically they were truant from their own schools. But they were here to drive home a point about the inequities between rich and poor schools in America's public education system.

In a nation where education is funded largely by local property taxes, schools in wealthy communities have plenty of funds to spend on programs that get their kids ready for college. Schools in poor communities scrimp and save to get the job done — or hope that funding from the state will help fill in the gap.

The problem is arguably at its worst in Illinois. In most places, state funding fills at least some of the gap between the richest and the poorest districts. Illinois ranks 49th in the percentage of school funding that comes from state government. As a result, many of the state's richest suburban districts spend $17,000 or more per student per year. In rural districts and urban communities, funding is drastically lower — with some districts spending less than $6,000 per student.

Look me in the eye and tell me I can't have new books and the resources these other schools have.

Some of the state's least-funded districts are in the state's mostly-white rural areas — but most are in communities of color. Of the 51 poorest districts in Illinois, more than half are majority-black. Three out of four African-American children and two-thirds of Latino children in Illinois attend school in a high-poverty district. A recent Washington Post article quoted Chicago Public Schools CEO Arne Duncan describing the situation as "totally separate and totally unequal."

So when Rev. James Meeks, a controversial pastor and senator in the Illinois State Assembly, convened a group of Chicago pastors to organize a citywide boycott of Chicago public schools, parents were eager to let their kids participate.

"Things have always been bad in Chicago, but our children do not have even the opportunities we had when we were growing up," said Chicago resident Evalina Crittle. "There aren't any activities. Even gym is being cut out of our schools. It's becoming genuinely unhealthy for our children."

Given the spotlight the boycott placed on New Trier, one might expect the boycotters to get a chilly reception in Winnetka — but that didn't happen.

"Rev. Meeks reached out to let us know this was not done to embarrass us, but to call attention to the fact that not every school has the resources we do," said New Trier Superintendent Linda Yonke. "We may disagree about his methods, but there is really very little disagreement about the state of funding in Illinois."

As Brandon and his fellow students stepped off the bus, newspaper reporters snapped pictures of the boycotters being warmly welcomed by Winnetka residents and school officials. It looked like a beautiful example of people coming together across social boundaries. But within the halls of New Trier, students actually had little contact with the protestors.

"The administration had decided that they didn't want this to interfere with our students' academic day," said New Trier social studies teacher Tom Kucharski. "There was talk about the protest, but here in the school it was almost like it wasn't happening."

Amanda Cohen wouldn't stand for it. New Trier's class schedule offered students a free period to work on social service projects, and Amanda wanted to know why she couldn't spend hers with the protestors.

"I went to the principal's office and asked about it," Cohen said. "I said, 'They're missing the whole first day of school to come here, so I don't see why I can't use my free period to go there."

Kucharski found a way around the problem, by agreeing to take a small group of students to a rally the protestors held after school.

After the rally, Brandon Saunders approached the New Trier students and the group began talking about the next steps they should take. Soon, the Illinois Council of Students was born.

Students Take Charge

As September wore on, Rev. Meeks continued his campaign to call attention to school inequity. He crashed a meeting of city leaders planning for a Chicago Olympics. He led a group of student boycotters onto the floor of the Chicago Mercantile Exchange for a round of teach-ins. He promised to ring Wrigley Field with orange-shirted student protestors at a Cubs playoff game.

Meanwhile, Brandon Saunders and his new friends at New Trier were hard at work on the next stage of the movement. They wanted their Illinois Council of Students to become a truly student-led movement in which kids took their concerns directly to the public. A handful of students, half from New Trier and half from various schools in the Chicago Public School system, sat down to draft a Student Bill of Rights. In the process, they wound up learning a lot about how the world looks from another person's perspective.

"One thing that surprised me was that they (the New Trier kids) were totally oblivious to the entire situation," Brandon said. "They really did not know other schools are not like theirs."

Resegregation and the Courts

In the K-12 curriculum, the story of school integration often starts and ends with Brown v. Board of Education. A series of lesser-known Supreme Court rulings have had just as much impact on the school lives of today's students — by setting the stage for the resegregation of American schools.

Keyes v. School District #1 (1973) — The Court rules that school systems do not have to integrate if they are segregated due to housing patterns rather than through a state mandate.

Milliken v. Bradley (1974) — The Court declares that predominantly-white suburbs do not have to participate in busing programs intended to integrate schools across an entire metropolitan area, as long as the suburbs have no past history of discriminating against students.

Rodriguez v. San Antonio Independent School District (1973) — Parents in a Latino community sue after discovering that their school district has approximately half as much funding, per pupil, as schools in a neighboring Anglo community. The parents say this violates their right to equal protection under the Constitution — but the Court rejects this by declaring there is no "right" to an education.

Some Questions to Consider

1. How did these rulings combine with the housing patterns of the last 40 years to create the school system we have today?

2. When someone buys a house, what effect does school quality have on that person's choice of where to live? What effect does that choice have on home prices? And what effect do home prices have on school funding?

3. What other countries recognize a "right" to education? If the United States recognized education as a right, how would that affect funding?

Brandon says he sees the New Trier students as a little naïve — but quickly follows it up by noting that he, too did not really understand the funding issue until he boarded the bus for New Trier.

"I guess I knew about it sort of — people in the community would say things like 'I guess the white school has this or that' — when you see it with your own eyes, there's a different insight," he said. "It's still sinking in."

The students are also learning how to navigate the sometimes difficult space between them. The New Trier students say they have been a little reluctant to associate themselves closely with Rev. Meeks, the boycott's leader, who has been known for making homophobic remarks. But when Meeks invited them to visit his congregation at Salem Baptist Church, they were eager to go. For some of the New Trier students, it was their first experience in a setting where they weren't in the racial majority.

"There was a little bit of processing about what it must be like to be a black person in a white community," Kucharski said. "That, by itself, is a big victory."

Kucharski says the relationship between his school and Meeks' church is so warm, he worries that students "will start to think that working for social justice is all handshakes and hugs."

But the students may get out of their comfort zone very soon. They plan to take their Bill of Rights on the road, traveling to schools around the state, meeting student leaders, swapping notes on school conditions and recruiting new chapters for their organization. They're zeroing in on underfunded districts in communities like Rockford and Peoria. And when they've built a statewide coalition, they're going to bring their demands to the Illinois State Assembly.

"Education is the motor to the car," Brandon said. "We need to make people understand that if we're not giving everybody a chance, we're hurting the whole country."

Student Bill of Rights

By the Illinois Council of Students

All Students Have:

1. The right to qualified, engaged and passionate teachers and unfettered access to textbooks and school supplies.

2. The right to be secure in their persons and their possessions.

3. The right to an emotionally safe environment.

4. The right to a physical space that encourages learning.

5. The right to an honest, accessible and engaged administration.

6. The right to an appropriate student-teacher ratio.

7. The right to programs that address academic and social needs.

8. The right to participate in clubs and sports.

9. The right to fair and equal school policies, and impartial enforcement of them.

10. The right to freely express ideas and beliefs.

For more information, or to join the organization, go to the Illinois Council of Students.

0 COMMENTS