In my article “Don’t Say Nothing,” I warn about the dangers of teachers being silent on the issue of racial violence. And what I love about this profession is that, when teachers do speak, when we take a stance and choose to engage in the political, we plant seeds for the next generation. When we teach in ways that promote respect, love, empathy and understanding—despite the difficulties we may face in doing so—we have the power to influence young people who will eventually become doers and leaders in this world.

Teaching about the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement allows each of us to chew on multiple injustices simultaneously. We are able to teach not only about racism, its history and its present manifestations, but we also are able to point to solutions and methods of action so our students don’t become disillusioned. When students are overcome with doubt, we can draw parallels to Standing Rock and say to them, “This is how people are fighting for change in spite of the obstacles they are experiencing.” We can talk about sexism and patriarchy, but we can also leverage conversations about sexuality using gender-neutral and affirming language.

Teaching about BLM isn’t just about police brutality and the ways an organization is seeking to end it. Bringing this movement to the classroom can open the door to larger conversations about truth, justice, activism, healing and reconciliation.

The work required to teach about Black Lives Matter is extensive and heavy, but this topic can be addressed effectively in classrooms—at any grade level.

Elementary Applications

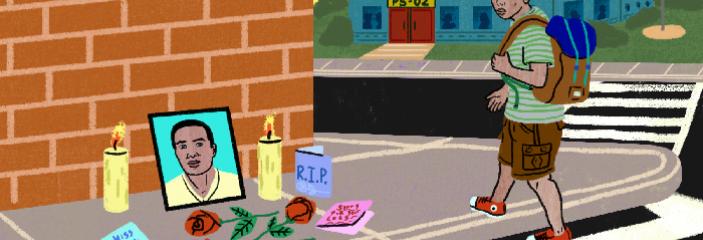

Trinity Thompson and her colleagues, who teach second grade in Harlem, knew they wanted to teach about the BLM movement. However, a couple of false starts made it clear that, for their efforts to be sustained and successful, they needed to establish safety and provide students with context. They decided to form a Cultural Competency Committee to educate themselves about social justice issues, build lesson plans and incorporate family input. The committee developed a six-month curriculum that focuses on education professor Bree Picower’s six elements of social justice curriculum design: self-love and knowledge, respect for others, issues of social injustice, social movements and social change, awareness raising, and social action.

“I think for me the biggest thing was providing both windows and mirrors,” Thompson explains, “having their community and their history, even in Harlem, reflected in what they’re learning … but also providing them windows. We looked at Stonewall, we looked at South Africa and we looked at Palestine.”

Thompson used text-based culture circles to initiate conversations about police violence and Black Lives Matter—a format she had already used with them throughout the curriculum. She began by reading to her students an age-appropriate text about what to do when bad things happen, then guiding them through a discussion, providing them the space and language they needed to process what they were experiencing. Thompson even took her students through Campaign Zero, a data-driven platform dedicated to ending police brutality in the United States. She admits that this was a difficult task, but she was able to make it work by referring to pictures on the Campaign Zero website.

Karen Shreiner, a second-grade teacher in Oakland, California, is another example. Shreiner works for a charter school network committed to equity and social justice. Because her students—like Thompson’s—are so young, Schreiner has found creative yet age-appropriate ways to immerse them in the discourse necessary to understand and process such serious subject matter. She embeds current topics into pre-planned units, allowing her to meet content and curriculum demands while also teaching pressing issues in meaningful ways. To introduce students to her unit on activism, she used an activity her students were familiar with: gallery walks. In this case, she used images that captured moments of resistance.

“I have pictures of everything from the March on Washington to when the Bay Bridge was shut down because of Black Lives Matter protesters a couple years ago,” Shreiner says. She has students go to each photo, then use questions and sentence frames they’ve practiced. “They can say things like, ‘I notice that _____’ or ‘I wonder why this person is _____’ or ‘I think this person feels _____ because _____.’”

Schreiner is careful not to tell her students what to think about the images, letting them come to their own conclusions. “A lot of them will notice things like, ‘Some of these pictures are from a long time ago. Some of them are from now,’” she recalls. “‘A lot of these pictures involve the police. A lot of the pictures involve the police treating people in ways that aren’t nice.’” If she hears students say things that reflect assumptions or implicit bias, she interrupts them to ask that they provide evidence. Her approach works, she says, because she establishes trust in her classroom and prepares students all year to talk about issues of identity, diversity, justice and action.

A Middle School Approach

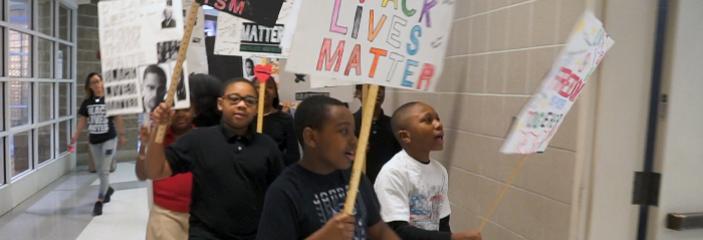

Middle school students attending after-school programming through Breakthrough Providence learn about Black Lives Matter not from classroom teachers but from other students. Dulari Tahbildar is the executive director of this Rhode Island-based chapter of a national collaborative focused on the needs of middle-level students from low-income households. The organization offers supplementary curriculum developed and taught by high school and college students who are preparing—with the support of Breakthrough—for careers in teaching. Tahbildar says the organization was unanimous in its decision to focus on Black Lives Matter during the 2016-17 school year.

“A lot of people don’t really recognize the voices and contributions of our youngest students,” Tahbildar says. “We’re working with 16- to 22-year-olds who don’t have any formal teaching experience, and we basically give them a crash course in ‘What is a lesson plan? What is an objective? How do you develop trusting relationships with students?’” The organization also emphasizes to its young teacher-students the importance of driving critical thinking and not telling students what to think.

I think that’s an important part of a young person’s education in life: to be able to talk about their own role as change makers.

The student-to-student resources that the budding teachers developed were so effective that Breakthrough Providence held a statewide gathering to encourage other middle school educators in Rhode Island to use the resources when teaching about Black Lives Matter. Tahbildar understands why some educators hesitate to address this movement but tells her fellow teachers, “Nobody should feel like they’re alone in this endeavor.”

Tahbildar hopes that Breakthrough Providence’s work will empower more teachers to educate themselves and take steps toward teaching about Black Lives Matter and other social justice movements. “Education is more than schooling,” she says. “I think that’s an important part of a young person’s education in life: to be able to talk about their own role as change makers.”

Teaching BLM in High School

For high school teachers, particularly those in the humanities, teaching about Black Lives Matter can be used to help students think critically about how resistance movements have been treated historically.

What distinguishes a rebellion from a riot? Whose murders are labeled genocide? What racial groups and tactics of resistance are praised over others? These are all questions worth exploring. Romanticizing the civil rights movement is a particular concern when it comes to what students have already learned. Prevailing narratives praise “respectable,” seemingly passive, docile, nonviolent Black leaders as heroes while condemning louder, more militant tactics, such as those associated with the Black Panther Party and the leadership style of Malcolm X. A related issue is that typical historical narratives about Black resistance often pit leader against leader and movement against movement, discounting the ways in which Black people have always resisted. Students need to know what links these movements, rather than what divides them. Desegregation and voting rights, like police brutality, mass incarceration and state-sanctioned violence, are all symptoms of the systemic racism that has plagued the United States since its inception.

Guiding high schoolers to identify how dominant historical narratives silence stories of resistance can help them make connections between the past and the present. It also can encourage them to see themselves as activists, and equip them with the knowledge they need to keep pushing our nation toward “a more perfect union.”

*This article was revised 1/24/2022 to capitalize the words Black and Brown.

0 COMMENTS