Policies reflect a school’s priorities and, like budgets, reveal as much in what they omit as in what’s written on the page. It’s time more LGBTQ kids see themselves on the page. School leaders who make inclusive policies a priority can set the tone for entire schools and districts.

Some policies that sound standard or fair on the surface can marginalize or discriminate against LGBTQ students. These examples point to aspects of school that can be tough for kids with queer identities—and offer ways to follow the law and create more equitable and inclusive policies.

Know Your Students’ Rights

Creating more inclusive policies begins with an understanding of students’ basic rights, as determined by the law and by educational best practices. These rights serve as the backbone of good policymaking and equip school leaders with a legal and moral defense against backlash.

- Students have a right to express their gender as they wish—regardless of their sex assigned at birth. While students must follow basic dress codes—e.g., no profanity on T-shirts—they cannot be forced to align with gender-specific guidelines. The same is true of hair length, makeup, prom attire, jewelry, footwear, etc. Gender-specific guidelines based on a student’s assigned sex violate a student’s rights to freedom of expression. As long as one student can wear an outfit without breaking rules, so can another.

- Students have a right to be free from discrimination or harassment based on religious views. LGBTQ students in public schools have equal rights to their peers, including the right to freedom from religious persecution. This means students can’t be denied equal access to safety and opportunity due to someone else’s religious beliefs.

- Students have a right to express LGBTQ pride. If your school’s dress code allows students to wear T-shirts with slogans or pictures, it’s unlawful for your school to ask a student to take off their shirt just because it endorses LGBTQ pride or makes a statement about their LGBTQ identity.

- Students have a right to form Gay-Straight or Gender and Sexuality Alliances (GSAs). If your school permits other student clubs, it should allow students to form and publicize a GSA.

- LGBTQ students have a right to attend proms, field trips and dances. Students cannot be denied equal access to school events or school learning opportunities because of their identity. Students also have the right to take a date of any gender to school dances as long as their date satisfies all attendance eligibility rules, such as age limits.

- Students have a right to access facilities and opportunities that match their gender identity. This includes bathrooms, locker rooms and gender-specific activities.

- Students have a right to be free of harassment and to have harassment treated seriously. Public schools must treat harassment or bullying that targets LGBTQ students with the same seriousness they would use in a case of harassment against any other child. Ignoring harassment and bullying is a violation of Title IX.

- LGBTQ students have a right to be “out.” Educators can always ask students to stop disruptive speech—in the classroom during a lecture, for instance. But schools cannot tell a student not to talk about their sexual orientation or gender identity while at school.

- LGBTQ students have a right not to be “outed.” Even if people within the school know about a student’s sexual orientation or gender identity, educators cannot disclose a student’s private information without consent. Outing LGBTQ students violates their constitutional rights and has led to tragic and fatal consequences.

Schools that successfully acknowledge these rights in their policies take important steps toward providing an environment where LGBTQ students can succeed, feel supported and have access to the same opportunities as their peers.

Anti-bullying/Harassment Policies

Research shows that LGBTQ students in schools with inclusive policies are less likely to experience harassment and more likely to advocate for themselves if they do. Naming LGBTQ identities within the policy is critical to promoting physical safety in your school.

An inclusive policy:

- Includes gender identity, gender expression and sexual orientation (actual or perceived) as protected, immutable identities, alongside race, religion, ethnicity, disability, etc. (Unfortunately this isn’t possible in South Dakota where, as of 2018, naming protected groups in anti-bullying policies is illegal.)

- Lays out a clear expectation that all incidents of bullying will be investigated seriously.

- Lays out a clear expectation that staff will intervene to stop all forms of bullying and harassment, and report incidents when they occur.

- Includes digital harassment within the scope of potential investigation and punishment, as students often face the worst bullying from peers online. According to GLSEN, nearly half of LGBTQ students face cyberbullying—a persistent threat that cannot be ignored by schools just because it sometimes occurs “off school grounds.”

- Makes it clear that students and educators will be held responsible for bullying behavior and protected from harassment.

Most importantly, these inclusive policies must be widely known. Make sure students, educators and the school community have access to the anti-bullying policy from the beginning of the year. This transparency clearly communicates the expectations to all students and educators and helps LGBTQ students feel safer and valued.

For an example of an exemplary policy, look at this excerpt from Minnesota’s model policy, recommended to schools in the state:

Bullying can be, but need not be, based on an individual’s actual or perceived race, ethnicity, color, creed, religion, national origin, immigration status, sex, marital status, familial status, socioeconomic status, physical appearance, sexual orientation, including gender identity and expression, academic status related to student performance, disability, status with regard to public assistance, age, or any additional characteristic defined in Minnesota Statutes, Chapter 363A (commonly referred to as the Minnesota Human Rights Act). Bullying in this policy includes “cyberbullying,” as defined below.

“Cyberbullying” is bullying that occurs when an electronic device, including but not limited to a computer or cell phone, is used to transfer a sign, signal, writing, image, sound or data and includes a post to a social network, internet website or forum.

Bathroom and Locker Room Access

Students should have access to bathrooms, locker rooms and other gender-specific spaces that best match their gender identity. Basing bathroom access on assigned sex can have dangerous ramifications for students whose gender expression does not match their assigned sex. According to a survey from UCLA’s Williams Institute, 68 percent of transgender people faced verbal harassment while in the bathroom; nearly 10 percent endured physical assault. Those who fear such harassment will often not go to the bathroom at all, risking their physical health.

Bathroom policies often ignore the identities and experiences of intersex students entirely. Biological or birth certificate criteria might force them to use facilities that do not correspond with their gender expression which, again, can violate their privacy and dissuade them from using these facilities at all.

A common pushback: “I am (or my child is) uncomfortable being in the bathroom with a transgender student.”

Be prepared to respond. Point out the difference between accommodation and discrimination. If someone is uncomfortable being in a shared space—for whatever reason—give them the option of a more private facility. Just remember that their discomfort isn’t justifiable cause to force another student to use a different bathroom or locker room. A gender-neutral or single-stall bathroom can be made available to any student—LGBTQ or not—who desires more privacy. If such a facility is available, make sure students know they have the option. At primary public-use bathroom locations, post a map that points to where students can find the single-stall or gender-neutral bathroom.

For an example of an exemplary policy, see the nondiscrimination addendum adopted by Atherton High School of Louisville, Kentucky, in 2014:

Guidelines on Accessibility for Students

[School Name] shall not discriminate on the use of school space as the basis of gender identity nor gender expression. The school shall accept the gender identity that each student asserts. There is no medical or mental health diagnosis or treatment threshold that students must meet in order to have their gender identity recognized and respected. The assertion may be evidenced by an expressed desire to be consistently recognized by their gender identity. Students ready to socially transition may initiate a process with the school administration to change their name, pronoun, attire, and access to preferred activities and facilities. Each student has a unique process for transitioning. The school shall customize support to optimize each student’s integration.

Inclusive Sports Policies

Schools should, to the best of their ability, allow students to play on sports teams and clubs that best match their gender identity. Sometimes this will run counter to the rules of your state’s high school athletics association. As of 2018, 17 state associations* have fully inclusive policies, allowing trans and intersex student athletes to participate with teams that correspond to their gender identity—without the requirement of hormone treatments or surgery.

School leaders in states with policies that require queer students to undergo medical interventions or legal changes can advocate for more inclusive options. Often, such policies cite competitive disadvantage as the reason for instilling such rules, especially in the case of transgender and intersex girls. However, not all students have the financial or social means to pursue medical intervention—and not all transgender or intersex people want to transition medically and physically.

Schools attempting to craft a more inclusive policy for sports participation should keep the following recommendations in mind:

- Students should be able to join intramural clubs and sports teams that correspond most closely with their gender identity.

- Students should have access to locker rooms that correspond most closely with their gender identity.

- Gender-neutral changing facilities, locker rooms and bathrooms can be offered to any student who feels uncomfortable changing among their peers, but should not be required as the only option for trans, intersex or nonbinary students. This segregates them.

- Anti-bullying and harassment policies should also cover the actions of coaches and athletes, with specific mention that bullying based on one’s gender, gender identity, gender expression or sexual orientation will not be tolerated.

- Students who do not publicly identify as trans or intersex have a right to not be outed to anyone—including peers and teammates—by their coach or school officials.

- When traveling, students should be assigned hotel rooms and roommates that correspond with their gender identity; any student who requests privacy should be accommodated while not singled out as demanding “special treatment.”

- Students should not be forced to wear gendered sports uniforms that conflict with their gender identity.

While the science behind hormones and perceived gender differences is more complicated than many people believe, the idea of trans and intersex students (without hormone treatment) competing alongside cisgender students may generate a lot of pushback from the community. Balancing gender inclusivity and “fair play” can seem difficult, and state rules may determine that teams are ineligible if they allow such participation. In such instances, we recommend schools consider three possibilities:

- They can ensure that intramural or non-sanctioned community sports are available to all students, regardless of assigned sex.

- They can look for local, co-ed leagues and participate.

- They can allow transgender and intersex athletes to practice, travel with the team and compete in exhibitions.

These are imperfect solutions, but schools should strive for the most inclusive option available to them, while continuing to advocate for more inclusive policies at the state or district levels.

School leaders in states where there is no policy or where the policy gives power to school districts should draft and suggest inclusive policies, such as the "eligibility to participate" guidelines for a model policy spelled out by Erin E. Buzuvis, director of the Center for Gender & Sexuality Studies at the University of New Hampshire.

Eligibility to participate: A student has the right to participate in athletics in a manner consistent with the sex listed on that student’s school records. A student whose gender identity is different from the sex listed on the student’s registration records may participate in a manner consistent with the student’s gender identity in accordance with the policy below.

Additional guidelines

The [state athletic association] endorses the following guidelines to ensure the nondiscriminatory treatment of transgender students participating in [state athletic association] activities.

- Changing Areas, Toilets, Showers. A transgender student-athlete should be able to use the locker room, shower and toilet facilities in accordance with the student’s gender identity. Every locker room should have some private, enclosed changing areas, showers, and toilets for use by any athlete who desires them … transgender students should not be required to use separate facilities.

- Hotel Rooms. Transgender student-athletes generally should be assigned to share hotel rooms based on their gender identity, with a recognition that any student who needs extra privacy should be accommodated whenever possible.

Or this example from the Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education:

Physical education is a required course in all grades. … Where there are sex-segregated classes or athletic activities, including intramural and interscholastic athletics, all students must be allowed to participate in a manner consistent with their gender identity.

*The states with fully inclusive policies are California, Nevada, Washington, Utah, Colorado, Wyoming, South Dakota, Minnesota, Florida, Virginia, Maryland, New Jersey, Connecticut, Rhode Island, Massachusetts, Vermont and New Hampshire. Elsewhere, states have varying rules. For example, in Alaska, the state association will honor the school district’s policy, inclusive or exclusive. In states like Delaware, Georgia, Illinois and New Mexico, associations require that students meet one or more of the following criteria: a legally changed birth certificate, a time period of undergoing hormone treatments and/or sex reassignment surgery. States like Iowa and North Dakota have different rules for trans boys and trans girls. And some states, such as Alabama and Kentucky, say sports participation must be determined by sex assigned at birth. Six states (Montana, Arkansas, Mississippi, Tennessee, South Carolina and West Virginia) have no policy at all. Transathlete.com maintains an updated list you can reference.

Dress Codes

In compliance with students’ legal rights, school dress code policies should allow for students’ free expression, including expression of their gender identities and pride in their queer identities. This means never targeting specific students’ identities with the dress code. If the gender expression or apparel worn by LGBTQ students is causing distraction, harassment or incidents of bias, this is a school climate problem—not a problem best solved by punishing LGBTQ students and suppressing their rights to free expression.

Dress codes should:

- Allow exceptions that promote a safe or comfortable learning environment, such as allowing athletic attire in P.E., tights in dance or gymnastics, or protective gear in science labs, workshops or art class.

- Prevent students from wearing attire that disrupts a safe learning environment, such as clothes that feature hate speech or pornography, target a specific group of people, or advocate for violence or drug use.

- Treat students equitably regardless of their sex assigned at birth. Clothes that are permissible for one gender should be permissible for students of all gender identities.

- Require the covering of body parts generally considered private.

Dress codes should not:

- Be different for boys and girls, or force students to dress based on their sex assigned at birth.

- Disallow shirts proclaiming pride in a student’s LGBTQ identity on the false grounds that it is “distracting” or “offensive language to some.”

- Vary based on a student’s weight, body type or appearance.

- Discriminate against headwear or hairstyles that might correspond with a student’s religious, racial or ethnic identities.

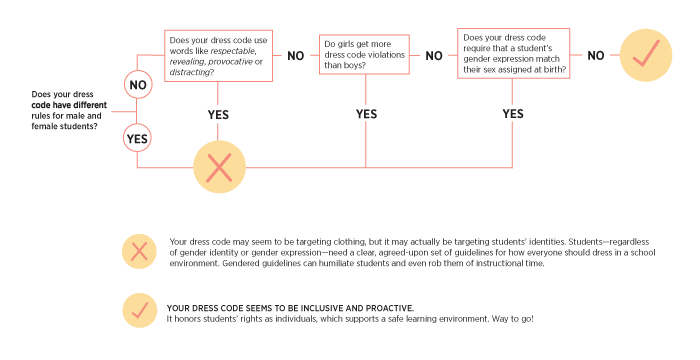

The graphic above, from “Controlling the Student Body,” provides a guide for leaders who want to ensure their school’s dress code is gender-inclusive.

An inclusive policy can look simple, such as the policy of Portland Public Schools.

PORTLAND PUBLIC SCHOOLS DRESS CODE POLICY

The District Dress Code policy applies to all schools in Portland Public Schools grades PK–12, with the exception of schools with a Uniform Dress Code policy. The responsibility for the dress and grooming of a student rests primarily with the student and his or her parents or guardians.

Allowable Dress & Grooming

- Students must wear clothing including both a shirt with pants or skirt (or the equivalent) and shoes.

- Shirts and dresses must have fabric in the front and on the sides.

- Clothing must cover undergarments, waistbands and bra straps excluded.

- Fabric covering all private parts must not be see-through.

- Hats and other headwear must allow the face to be visible and not interfere with the line of sight to any student or staff. Hoodies must allow the student's face and ears to be visible to staff.

- Clothing must be suitable for all scheduled classroom activities including physical education, science labs, wood shop and other activities where unique hazards exist.

- Specialized courses may require specialized attire, such as sports uniforms or safety gear.

Non-Allowable Dress & Grooming

- Clothing may not depict, advertise or advocate the use of alcohol, tobacco, marijuana or other controlled substances.

- Clothing may not depict pornography, nudity or sexual acts.

- Clothing may not use or depict hate speech targeting groups based on race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, gender identity, religious affiliation or any other protected groups.

- Clothing, including gang identifiers, must not threaten the health or safety of any other student or staff.

- If the student’s attire or grooming threatens the health or safety of any other person, then discipline for dress or grooming violations should be consistent with discipline policies for similar violations.

Inclusive Sex Education

Most LGBTQ students face a void when it comes to sex education—a void they often fill with inaccurate and age-inappropriate resources online. According to the Guttmacher Institute, only 12 states require the discussion of sexual orientation in sex ed; three of those states (Alabama, South Carolina and Texas) require that all coverage of queer sexual orientations be negative in nature.

This gap in our teaching negatively affects LGBTQ students, who, according to the CDC, are already at greater risk for intimate partner violence, sexual assault, STIs and negative feelings about their bodies. These risk factors underscore the need for inclusive sex education that positively covers LGBTQ identities. This also benefits non-LGBTQ students who otherwise may not understand their peers.

Providing comprehensive sex education is nearly impossible for educators and school leaders in states where so-called “No Promo Homo Laws” prohibit teachers from discussing LGBTQ topics in the classroom. (As of 2018, these states included Arizona, Texas, Oklahoma, Mississippi, Alabama and South Carolina). Educators in these areas can advocate for changes in state law and reach out to civil rights organizations that may want to represent LGBTQ students and teachers facing this discrimination.

For educators in all states, pushing for more LGBTQ-inclusive sex ed requires a plan. Here are some tips for making sure the initiative is taken seriously:

- Partner with community organizations. They often have more resources and may have also identified gaps in your school and district policies.

- Include student voices. Encourage students to advocate for their own education, and you’ll have strong allies throughout the process.

- Attend school board or community meetings. Identify potential allies and possible counterarguments. Don’t forget to indicate if you’re there in an official capacity (with permission from your school) or as a private citizen.

- Push boundaries. If your school board can’t make changes due to state legislation, encourage members to pass a resolution calling for improved sex education. The resolution can help state-level advocates push for legislative change.

Comprehensive and inclusive sex ed includes:

- Discussion of gender identities and sexual orientation—and not just as a special topic, but included throughout the coursework.

- Examples of healthy relationships, including same-sex relationships.

- Examples of diverse family constructions, including families with same-sex couples.

- Countering stereotypes about gender roles, LGBTQ identities and what it means to be a man or woman.

- Information for safe and protected sex practices for people of all identities.

- Medically accurate, myth-free and age-appropriate information on sexually transmitted infections, including HIV/AIDS.

- Messaging that does not assume students’ sexual orientations and gender identities, and that covers LGBTQ topics whether students in the class are “out” or not.

For more recommendations, see the National Sexuality Education Standards.

Knowing Your Role as an Ally

Following these four guidelines will put you in the best position to stand alongside your queer students:

Good allies begin with self-reflection.

Being an effective LGBTQ ally requires significant self-reflection and a strong sense of one’s own relationship with gender identity and sexual orientation. Before spreading this work throughout your school, begin within.

Take time to consider these questions:

- When did I become aware that I had a gender? When did I first become aware of my sexual orientation?

- What messages did I learn about sexual orientation or gender growing up?

- Was my sex, gender identity or expression ever in conflict with activities I wanted to participate in?

- Did my sexual orientation (or the fear of being perceived to have a different sexual orientation) ever keep me from participating in certain activities or social situations?

- Did I ever feel pressure to conform to cultural expectations related to my gender? Did I ever feel pressure to perform or hide my sexual orientation in any way?

- Did I ever judge others for not conforming to these cultural norms? If so, where did these beliefs or judgments originate?

- What messages—both implicit and explicit—do I convey to my students about sexual orientation or gender?

- Was there ever a time I wanted to challenge or transgress gender norms? What was the outcome and why?

Once you’ve had a chance to self-reflect on your experience, take an honest self-assessment of your readiness to talk about these topics with students or colleagues.

- Talking about gender or sexual orientation is challenging because…

- Talking about gender or sexual orientation is necessary because…

- Talking about gender or sexual orientation is beneficial because…

When talking about sexual orientation with students, which of the following choices fits your comfort level?

- I am almost always uncomfortable.

- I am usually uncomfortable.

- I am sometimes comfortable, sometimes uncomfortable.

- I am usually comfortable.

- I am almost always comfortable.

When talking about gender identity with students, which of the following choices fits your comfort level?

- I am almost always uncomfortable.

- I am usually uncomfortable.

- I am sometimes comfortable, sometimes uncomfortable.

- I am usually comfortable.

- I am almost always comfortable.

If you find yourself listing a lot of challenges and leaning toward the “uncomfortable” end of the spectrum, focus on the sections from this guide titled Be Willing to Learn Essential Terms; Facilitate Conversations About Identity With Care; Challenge Gender Norms and Lead Discussions with Courage and Care. Our publication Let’s Talk! is a good starting point for doing this internal work before diving deeper.

Good allies speak up against bullying, homophobia, transphobia and harassment.

Chances are high that homophobic or transphobic bullying or harassment is occurring in your school.

One of the most effective things you can do is respond directly to homophobic or transphobic behavior. This includes remarking on the use of slurs and other phrases, such as “That’s so gay.” Here are four approaches you can use:

- Interrupt. Speak up against biased remarks, every time, without exception.

- Question. Ask simple questions to learn why the comment was made and how it can be addressed.

- Educate. Explain why a word or phrase is hurtful or offensive and encourage the speaker to choose different language. Help students differentiate between intent and impact.

- Echo. While one person’s voice is powerful, a collection of voices incites change.

Respond to biased or homophobic behavior as if there is an LGBTQ student in the room at all times. After all, educators can never fully grasp the extent to which students are listening or how deeply they are affected by harmful words.

For more practical advice on speaking up against biased language and intolerance from students, administrators and peers, see our guide Speak Up at School.

Teachers can also encourage students to respond to bullying or bias incidents as a community to promote unity, improve school climate and raise awareness. To help assess the severity of the problem, for example, students can gather together to conduct a survey on hurtful language used at school. Student groups can also organize an assembly or a march, observe GLSEN’s Day of Silence or plan another campaign about the damaging effects of hurtful words.

Good allies don’t try to do this work alone.

One way to preempt backlash or prevent feeling alone in this work is finding other allies in your school. Let administrators, teachers and counselors know your plans. Secure their support ahead of time. Work together to ensure content meets academic criteria and expectations. These conversations provide an entry point for building a community of support and collaboration across the school.

Good allies foster an inclusive and empowering environment.

At the end of the day, skilled educators strive to make their schools and classrooms safer spaces so meaningful, constructive and rewarding social, emotional and academic learning can take place for everyone involved. In these spaces, students are encouraged to value their own individuality while also learning to value the unique experiences and perspectives of others.

“When I act courageously in the classroom, I express my sense of trust in my students. Trust is actually the most important quality of a safe space for an LGBTQ student.”

—Peter J. Elliott, “How to Craft an Open Classroom”

An Inclusive and Empowering Environment

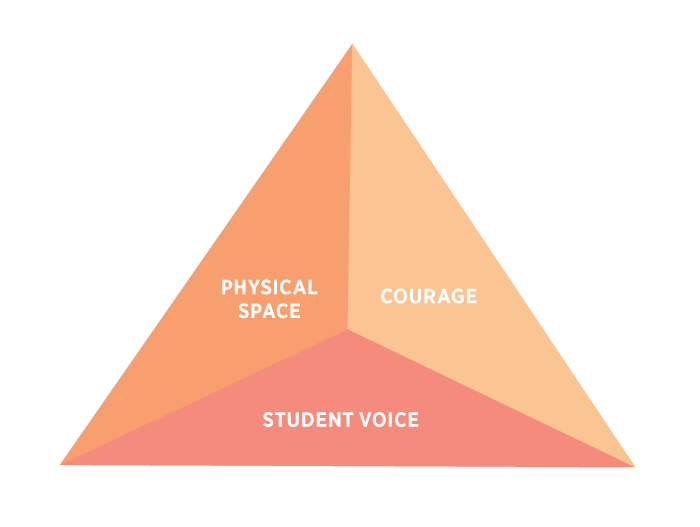

This triangle of inclusion will ensure an optimal, supportive learning environment is in place.

Point 1: Physical Space

Use visual aids such as quotation walls, posters of queer historical and literary figures, safe space stickers or other resources to serve as a consistent reminder to students that they are fully welcome.

Point 2: Student Voice

Encourage students to speak their truth. Structure discussions so that all students, introverted and extroverted alike, have equitable opportunity to share. Use a variety of storytelling methods so that all students—including LGBTQ youth—have a chance to tell their lived experiences.

Point 3: Courage

It takes courage to be an educator ally. Be willing to take risks with your students, and appreciate their bravery as they engage with the hard work of anti-bias education. It’s normal to get nervous; congratulate yourself for your commitment to telling the whole truth.

ASK TT

What do I do if…

The Community Pushes Back?

Here are some basic tips if your school, your colleague or you face an organized or sizeable backlash to LGBTQ-inclusive practices. For more tips and details, read our article “Teaching From the Bulls-eye.”

- Know the landscape of hate. Be aware of local and national hate groups that actively target schools over LGBTQ-inclusive practices. For example, the Liberty Counsel has organized letter campaigns and even hassled individual teachers to pressure educators into resisting things like inclusive sex ed. The Alliance Defending Freedom is another group heavily organizing against practices such as allowing trans students to use facilities that match their gender identity. In some cases, both groups offer free legal counsel to sue the schools. Arm yourself with information so you can counter their misleading messages.

- Find allies in your community. Build relationships with local business leaders, places of worship, sports teams or organizations who support inclusivity, and who can show that support in a public, influential way.

- Support the targets. If outside groups or online communities target particular students or student groups, bring those students together and give them an opportunity to express their feelings. Let them know that you support them, even after the worst is over. Provide counseling and additional security if needed. Make sure public statements do not draw a false equivalency between the demands of hate groups and the needs of LGBTQ students.

- Do not let misinformation go unchecked. Outside groups may respond to the implementation of best practices with untrue accusations. Inform students and families of misinformation being spread in the community, and set the record straight through your usual channels of communication.

Here are some of the most common examples of “pushbacks”—and ways to respond.

“I believe being gay or transgender is a sin; schools should not promote it.”

Response: Those who advocate for inclusive school environments for LGBTQ students are not asking you to forfeit your religious beliefs. Nor are sexual orientation and gender identity things to be promoted; they are innate. Just as LGBTQ students should not be pressured or bullied into expressing an identity that isn’t their own, we would never ask a cisgender or straight-identifying student to hide or change their true self.

Advocates are asking schools to take a stand against anti-LGBTQ harassment and its damaging effects on the educational outcomes for LGBTQ students. We hope most people can agree that all students should be able to attend schools free of verbal and physical harassment and can understand that a school serves a diverse population. School leaders must value all cultures and identities in the curricula and policies—without playing favorites.

We have the constitutional right to exercise our own religious beliefs in our lives (or to exercise none at all), and we are charged with a responsibility to protect the rights of others to hold religious beliefs as they choose. This is a core tenet of our democracy and a great civics lesson for us all. Public schools must strike that balance. They cannot privilege a dominant culture or religion while simultaneously denying equitable opportunity and safety to other students.

“LGBTQ students are getting special rights and preferences.”

Response: Creating a school climate that reduces anti-LGBTQ harassment and increases empathy for LGBTQ people enriches the lives of all students. Straight, cisgender students can still suffer or endure bullying because of strict gender norms and homophobia.

LGBTQ-inclusive curricula, practices and policies do not give additional rights to LGBTQ students. They simply fill gaps where LGBTQ students deserve the rights that their straight, cisgender peers already have. Straight, cisgender students already see themselves in curriculum. Straight, cisgender students already have access to bathrooms and locker rooms that match their identities and within which they can feel safe. And aspects of straight, cisgender students' identities, such as race and gender, are already covered by anti-bullying and harassment language. Adding LGBTQ people to these spaces does not erase their peers who are already there; instead, it brings them together.

“It’s not appropriate to talk about sex in the classroom.”

Response: While there are appropriate spaces to talk about sex in schools—in sex education or health classes, for example—talking about LGBTQ issues is not the same thing as talking about sex. Like heterosexual identities, relationships or feelings, LGBTQ identities, relationships and feelings are fundamentally about love and affection between human beings. If we can talk about one identity, we can talk about others.

Gay-Straight and Gender and Sexuality Alliances are also not about sex. Rather, they provide a space for people with a common interest, be it exploring culture and identity, sparking conversations, creating a respectful community, or activism.

“If GSAs are allowed, you have to allow students to form any club with a collective purpose, like a Neo-Nazi club.”

Response: There is a distinct difference between affinity groups (which bring people of shared experiences or cultures together) and groups that promote hate, harassment and exclusion. Schools have a right to disallow clubs that contribute to a disrupted education and unsafe school environment for some students. GSAs do neither; they promote inclusion and make school climates more equitable.

Prepare to speak up when you hear myths and misinformation.

Myth: “No one is born gay.”

Facts: The American Psychological Association (APA) states that “most people experience little or no sense of choice about their sexual orientation.” In 1994, the APA wrote that “homosexuality is not a matter of individual choice” and that research “suggests that the homosexual orientation is in place very early in the life cycle, possibly even before birth.”

Myth: “Gay people can choose to become straight.”

Facts: “Reparative” therapy has been rejected by all established and reputable American medical, psychological, psychiatric and professional counseling organizations. As early as 1993, the American Academy of Pediatrics stated that “[t]herapy directed at specifically changing sexual orientation is contraindicated, since it can provoke guilt and anxiety while having little or no potential for achieving change in orientation.”

Myth: “Transgender identity is a mental illness.”

Facts: Although transgender identity is not itself an illness, transgender people may experience mental health issues because of discrimination and disapproval. But these illnesses do not cause—nor are they caused by—transgender identity. They result from social exclusion and stigma.

Myth: “Students are too young to know their gender identity or sexual orientation.”

Facts: While a child’s concept of self may change over time, this isn’t because they are changing their minds. LGBTQ youth must navigate many social barriers and norms to come to terms with and accept their queer identities. This doesn’t mean they don’t recognize their identities at an early age; often it isn’t until later in life that they feel comfortable or safe to be their authentic selves.

Children do not need to be pubescent or sexually active to “truly know” their gender identity or sexual orientation. This is an expectation we do not place on straight, cisgender students. In reality, children often know their gender as early as 2 or 3 years old. Moreover, research suggests that allowing young children to align their gender identity with expression is associated with better mental outcomes among transgender children.