We ain't asking for anything that belongs to those white folks. I just mean to get for that little black boy of mine everything that any other South Carolina boy gets. I don't care if he's as white as the drippings of snow.

The Rev. J.W. Seals, Summerton, SC, 1953

It is, on its face, a story of separateness.

It is the story of two little girls walking through a railroad switchyard in 1950s Topeka, Kansas, lunch bags in hand, unable to attend a nearby white school, making their way to the black bus stop beyond the tracks.

And it is the larger story of countless other African-American children walking great distances, against great odds, to reach their own segregated schools as buses filled with white children passed them by.

But it is, at its heart, a story of togetherness, of courageously good-hearted and open-minded black and white people—and others—working together toward a constitutional ideal.

"When you look at Brown you are looking at a moment so powerful it is the equivalent of the Big Bang in our solar system," says historian and commentator Juan Williams. "It led to the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. It led to sit-ins and bus rides and freedom marches. And even today, as we argue about affirmative action in colleges and graduate schools, the power of Brown continues to stir the nation."

This year marks the 50th anniversary of the Brown v. Board of Education decision. On May 17, 1954, the U.S. Supreme Court struck down the separate but equal doctrine in American public schools.

The 11-page decision—much shorter than other major decisions of the era, and written by Chief Justice Earl Warren in purposefully unemotional language—was firm and clear: "We conclude that in the field of public education the doctrine of 'separate but equal' has no place. Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal."

The decision was unanimous. Reaction was not. Newspaper editorials variously praised and condemned the decision. White Southerners vowed opposition. Predictions of ugly resistance came true.

Color lines, certainly, had already been crossed by 1954. Jackie Robinson, for example, had made history on the baseball field the previous decade.

But for those who resisted integration, watching a sport was very different from sending a child to school. Because opposition was fierce, those who fought for integration faced tremendous hardships. Often they lost jobs, were denied credit and were ostracized in white—and sometimes even black—society.

The half-century since Brown has been a series of gains and losses, from segregation to integration and on to a new kind of segregation. Other movements—feminism, the fights for other minority rights, LGBT rights, the rights of people with disabilities—were aided, bolstered and fueled by Brown. And while Brown focused on schools, it also helped in the fight for desegregation of everything from public golf courses to public buses.

On one hand, Brown remains the hallmark of the promise of equality for this nation. On the other, Brown's promise remains, if not broken, certainly unfulfilled.

The road to Brown

It's fitting that Linda Carol Brown and younger sister Terry Lynn had to walk along railroad tracks for their daily journey to school, fitting that so many other children determined to have an education journeyed such long paths to school. The route to Brown was similarly long and arduous, court cases linked together, steaming forward to a destination countless miles away.

The NAACP's Legal Defense Fund pulled the train. In the mid-20th century United States, the NAACP was the most powerful civil rights organization, with membership growing tenfold in the 1940s, to nearly half a million.

And Thurgood Marshall served as conductor, the lead NAACP attorney for Brown and the mastermind behind much of its strategy. Marshall would later become the nation's first African-American Supreme Court justice.

Brown itself was made up of five separate but similar court cases in four states and the District of Columbia, representing tens of families:

- Briggs v. Elliott in South Carolina;

- Davis v. County School Board of Prince Edward County in Virginia;

- Gebhart v. Belton (a collection of cases itself, sometimes cited as Belton v. Gebhart or Bulah v. Gebhart) in Delaware;

- Bolling v. Sharpe in the District of Columbia (which ended up with a separate court decision); and

- The actual Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka in Kansas.

These cases had been working their way through state and federal courts for several years. Details varied and strategies differed, but each case attacked the forced segregation of black students.

Other cases—Cumming v. Richmond (Ga.) Board of Education, Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, Sipuel v. Board of Regents of the University of Oklahoma, Sweatt v. Painter, and McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents for Higher Education—were precursors to Brown, earlier attempts at integration and equal rights. (See timeline.)

And two 19th-century Supreme Court cases had created the laws that Brown sought to overturn:

- 1896's Plessy v. Ferguson, which opened the door to state-sanctioned racial discrimination across the South.

- And 1857's Dred Scott v. Sanford, which ruled that black people, enslaved or free, were "so far inferior that they had no rights which the white man was bound to respect."

Reacting to Brown: Hope and hatred

When the Brown decision was announced, the Chicago Defender, a long-standing African-American newspaper, printed this: "Neither the atom bomb nor the hydrogen bomb will ever be as meaningful to our democracy as the unanimous declaration of the Supreme Court that racial segregation violates the spirit and the letter of our Constitution."

While fear of reprisal kept many black people from celebrating publicly, the decision still inspired tremendous emotion. James T. Patterson's book, Brown v. Board of Education: A Civil Rights Milestone and its Troubled Legacy, describes one reaction:

Sara Lightfoot, a 10-year-old black girl, vividly recalled the moment that news of Brown reached her house. "Jubilation, optimism and hope filled my home," she wrote later. "Through a child's eye, I could see the veil of oppression lift from my parents' shoulders. It seemed they were standing taller. And for the first time in my life I saw tears in my father's eyes."

But not all African Americans celebrated. Some worried that desegregation would further alienate black people in white society; that it would lead to the elimination of jobs for black school teachers; that it would do little to eliminate the racism in people's hearts and minds.

Zora Neale Hurston, a noted African-American author, put it this way: "How much satisfaction can I get from a court order for somebody to associate with me who does not wish me near them?"

Among white people, many in the North and West, unaffected by the ruling, still saw it as positive. Conversely, white southern leaders and southern newspapers loudly and angrily denounced the decision.

Consider the May 18, 1954, editorial in the Jackson, Miss., Daily News:

Human blood may stain Southern soil in many places because of this decision, but the dark red stains of that blood will be on the marble steps of the United States Supreme Court building. White and Negro children in the same schools will lead to miscegenation. Miscegenation leads to mixed marriages and mixed marriages lead to the mongrelization of the human race.

Georgia Gov. Marvin Griffin said, "No matter how much the Supreme Court seeks to sugarcoat its bitter pill of tyranny, the people of Georgia and the South will not swallow it."

Such harsh words foreshadowed the difficulty of implementing Brown.

"With all deliberate speed"

Brown was actually decided in phases. After striking down Plessy and declaring segregation unconstitutional, the Warren Court handled the issue of implementation separately. Brown II, as it has come to be known, was handed down more than a year later, on May 31, 1955.

In that decision, the Supreme Court sent all cases back to lower courts, asking states to desegregate their schools "with all deliberate speed."

An earlier draft of the ruling had used the words "at the earliest practicable date," but that language was struck down, in part as an appeasement to the anticipated resistance of the South. Using the more open-ended "deliberate speed" wording, Brown set no deadlines and left much of the decision-making in the hands of local school officials.

From 1955 to 1960, federal judges would hear more than 200 school desegregation cases. Border states reached 70 percent integration within about two years. Southern states, from grade to graduate school, were hardly changed:

- In 1956, Autherine Lucy, a black woman seeking admission to the University of Alabama, was called vile names and pelted with rotten eggs by angry white people. Officials excluded her from campus, then expelled her. The university remained all white until the early 1960s.

- In 1957, bloody riots erupted as nine black students attempted to enter Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas. President Eisenhower, a reluctant player in the extended battle, eventually surrounded the school with 1,100 soldiers from the U.S. Army and the Arkansas National Guard. Troops stayed all year.

- In 1960 in New Orleans, armed marshals shielded 6-year-old Ruby Bridges as she passed an angry crowd of 150 white people who threw tomatoes and eggs.

- And by 1964 in Prince Edward County, Virginia—a full decade after Brown—not a single black child had been admitted to a white school. In fact, the county defiantly closed its public schools for five years rather than integrate them.

"Sleepwalking back to Plessy"

The passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 finally gave some teeth to Brown. That act, supported by the executive branch, empowered the federal government to cut funding to schools that continued to segregate their students and gave the U.S. Department of Justice authority to file lawsuits seeking desegregation of schools.

As Supreme Court Justice Hugo Black wrote at the time, "There has been entirely too much deliberation and not enough speed in enforcing the constitutional rights which we held in Brown."

But even then, integration was fought in a variety of ways. Using the fact that, legally speaking, Mexican Americans were considered "white," schools in Texas and other states created "integrated" schools of Mexican Americans and African Americans, leaving all-white schools unchanged.

It wasn't until 1971 that widespread integration began. That's when a North Carolina case—Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education—allowed school systems to bus students as a way of integrating schools in segregated neighborhoods. Busing remains a volatile issue, but this decision is the one that prompted the highest levels of integration.

The number of black students attending majority-white schools in the South rose from 2 percent in the mid-1960s to nearly 45 percent in the late 1980s, the peak of school integration.

But success brought other changes. The mid-1980s also saw the first lifting of federal court sanctions, allowing schools to return to racial segregation. By 1991, integration levels had returned to pre-1971 levels.

Gary Orfield of Harvard University's Civil Rights Project put it this way: "We are, in essence, sleepwalking back to Plessy."

The 1970s through the 1990s also spotlighted new forms of segregation, fueled by a history of so-called "white flight" from cities to suburbs, particularly in the North and Midwest. By the opening of the 21st century, the nation's most segregated public schools were found not in the South but in Illinois, New York and New Jersey.

There, and in other areas across the country, black and Latino students live in segregated, urban neighborhoods and attend overcrowded, under-funded, low-achieving schools, while most of their white counterparts attend affluent, nearly all-white schools in suburban America.

Separate and unequal continues: More than 80 percent of black and Latino segregated schools are in high-poverty areas, compared with 5 percent of segregated white schools.

Today, the arguments are about affirmative action and the disparities created by the use of property taxes to fund schools. Just last year, the Supreme Court offered a split decision on affirmative action admissions to college, upholding race-based admissions at the University of Michigan's Law School but striking down a similar process used for Michigan's undergraduates.

The issues have changed, but the fundamental question remains: How equal are American educational opportunities?

So many things

In the end, Brown is as simple as equality and as complex as justice.

Brown is the courage of Barbara Johns, a 16-year-old girl in Farmville, Virginia, who in 1951 led a black student walkout of 450 young people, shaming adults into taking up the cause of integration. As one of the Brown lawyers explained at the time, "We didn't have the nerve to break their hearts."

It is the activism of Esther Brown, a white Jewish woman who, along with the NAACP, fought school segregation in several Kansas cities, becoming herself a target of white hatred.

It is the persistence of McKinley Burnett, the Topeka NAACP president who, well before the Brown case, tried to persuade the Topeka Board of Education to integrate its schools.

It is the hindsight of Kenneth Clark, a psychologist who testified in Brown about the harm done to black children by segregation. Forty years after Brown, Clark wrote that the United States "likely ... will never rid itself of racism and reach true integration. While I very much hope for the emergence of a revived civil rights movement with innovative programs and dedicated leaders, I am forced to recognize that my life has, in fact, been a series of glorious defeats."

It is all those children of color, in so many states, moving with determination and hope toward the promise of equal education.

And it is those two little girls in Topeka, walking on the packed earth of a railroad switchyard, reminding us all that education in this free land is less free for some children than it is for others, the journey longer, more fraught with pitfalls, then and now.

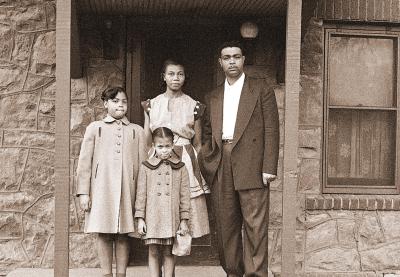

Photograph by Carl Iwasaki/Time-Life Pictures

Beyond Black and White

All five of Brown v. Board of Education's cases involved African-American plaintiffs. But the historical legacy and aftermath of Brown drew from a richer cultural and political spectrum.

There was 1927's Gong Lum v. Rice in Mississippi, in which a Chinese-American girl fought for the right to attend the white school rather than the black school. The Lum family made the case that the girl wasn't black. The court ruled she wasn't white, allowing school officials to categorize children as they saw fit.

In the 1940s—but still predating Brown—there was Mendez v. Westminster School District, when a Mexican-American family fought for and won the right to attend integrated schools in California.

The NAACP closely watched the California case, since its concerns mirrored those of the cases that would become Brown. Earl Warren, the man who would later write the Brown decision, was governor of California at the time.

The California case illustrated the layers of segregation and oppression present in the mid-20th century United States. The Mendez family had moved into the district in which their children faced discrimination because they were called on to oversee the farm of a Japanese-American family who had been interned during World War II.

Similar stories are found at the time of the Brown decision. In one school district in rural Texas in the mid-1950s, Mexican-American students were held in Spanish-language classrooms—even if they were able to speak English—in first and second grades before being integrated with white students.

Most Mexican-American students were kept in first grade for four years, followed by several years in second grade. Most students reached third grade at precisely the age they dropped out to go to work with their families in the fields.

In 1957, a court ruled the practice was "purposeful, intentional and unreasonably discriminatory" and ordered a new system for assigning students.

Brown, too, would be used to wage battles for inclusiveness on behalf of children with disabilities. At the time of Brown, nearly every state prohibited children with epilepsy from attending public school, even though medications were available to control seizures.

In praising Brown, Lillian Smith of Clayton, Georgia, wrote this in a 1954 letter to the New York Times: "All these children, some with real disabilities, others with the artificial disability of color, are affected by this great decision."

Activities

This article is a concise examination of school segregation, the Brown case and its relevance in the ongoing struggle for school equity. Build on this history using one or more of the following activities.

1. The Supreme Court concluded in its Brown decision that "separate educational facilities are inherently unequal." Using the web or school library, research how the resources of segregated schools differed. Construct 3-D models of a white school and a school for children of color in the pre-Brown era.

2. Create songs, raps, poems or spoken word pieces about the legacy of Brown. Host a school assembly to showcase students' work.

3. Pretend it's May 17, 1954. Write the front-page headline and lead story for your local newspaper. Use poster board or multimedia to display students' stories—contrasted against the front page that actually ran in your community newspaper.

0 COMMENTS