When Bessie Alexopolous and her parents moved from Greece to the United States, she didn't know a word of English. As the only Greek-speaking student in her class, Alexopolous was all but ignored by her teachers. Her fellow students followed suit.

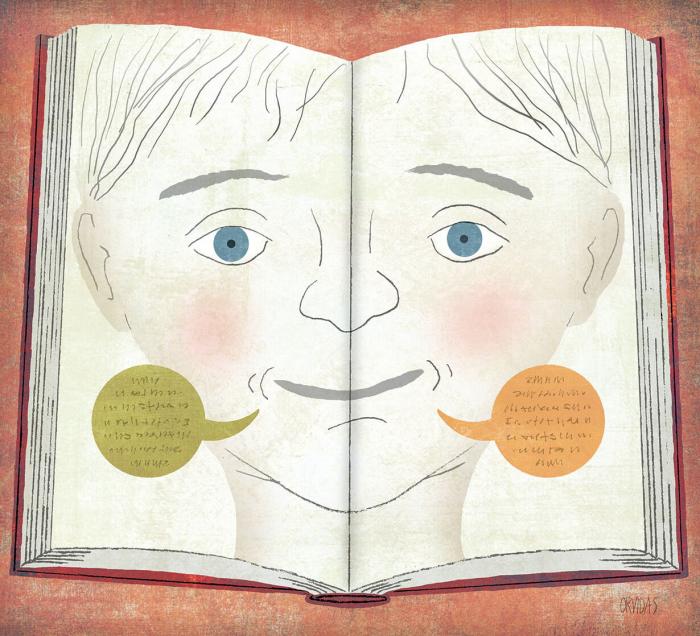

"I was silent for a long time," she says. "I was afraid to raise my hand. They always labeled me as shy, but the truth was I felt odd and different. And I didn't want to tell anyone that I spoke a different language at home."

Alexopoulos recalls her experience "all the time" in her adult life as a teacher in an ELL (or English language learner) program in Milwaukee. She works with other teachers to make sure, as she puts it, "social segregation doesn't happen."

"When students from different languages learn together, side by side, it helps the students feel valued. And when a student feels valued, it gives them a boost of acceptance, confidence and pride," Alexopolous says. "That's at the root of learning. If a teacher doesn't do that, a child will stay silent — just like I did."

Time to Make Friends

When English language learners don't speak in class or make friends outside their language group, teachers often attribute the problem to something in the student's cultural background. It's possible, however, that our method of teaching ELLs is a big part of the problem.

Teacher and researcher Barbara Hruska discovered this during a qualitative study of friendships in a New England kindergarten. The children in the study spent much of their time name-dropping, bragging about their number of friends, and recruiting new ones, Hruska found.

As the school year progressed, ELL students fell behind in this game, even though Hruska found no evidence of bias from English-dominant peers.

Finally Hruska realized the school's approach to teaching ELLs was the cause. By pulling ELL students out of class for separate instruction, the school was robbing the children of important contact time with potential friends. Visiting another student at home was also an important bonding experience for kindergartners, and Hruska found that non-English speaking parents rarely got the chance to arrange "play dates" with English-dominant parents.

Introducing Spanish-language classes for English speakers didn't help. Kids who already spoke Spanish were excluded from the class, reducing their "face time" even further and denying them a chance to be recognized as experts in a subject.

"How long will students of any age continue to participate in educational settings that do not offer supportive social relationships?" Hruska wrote.

As the nation's ELL population continues to rise, more educators are beginning to grapple with that question. From urban centers to small towns, schools are redefining the ELL experience, which once called for segregating language-learners into their own classes.

A growing number of schools are trying to roll back that problem by launching "social inclusion" efforts — programs that allow ELL students to learn as equals alongside English-speaking peers, in ways that value the skills and abilities of everyone.

"Social interaction in the classrooms means students will do well academically. It's an important way students learn respect and curiosity," says Rosanna Boyd, vice president of the National Association for Bilingual Education and director of the bilingual certification program at the University of North Texas. "Programs outside the classroom serve a different purpose: It's about [students] understanding who they are, their identity, [and] what they can contribute to their new society."

The stakes are high. Betina Johnson, a family advocate at Cedar Valley Community School in Lynnwood, Wash., knows this. She emigrated from Argentina 16 years ago.

"When I look at my students, it's like I'm looking in the mirror," Johnson says. "At first you are homesick. You miss family and friends. But the hardest part of living in a different country is the language barrier. Because you know you have to learn the language in order to survive."

Inclusion in the Classroom

At La Escuela Fratney, a Milwaukee, Wis. public elementary school, an in-school inclusion program is proving that social inclusion can help students blossom into their full potential.

Here's a typical scene from Fratney: in a second-grade classroom, Spanish- and English-dominant students crowd around as their teacher reads from a book propped open on her lap.

The teacher pauses and asks a question in Spanish. Four ELL students pop their hands into the air, eager to answer. When called on, they speak with confidence. The English-dominant students lean forward, looking to their ELL classmates for guidance. Later the tables will be turned, and the English-dominant students will teach their Spanish-speaking peers.

The approach, says principal Rita Tenorio, "levels the playing field. Kids who speak Spanish aren't seen as remedial— they're seen as a valuable resource."

All courses at Fratney are taught in Spanish and English. It's an example of dual-language education, a growing national trend. More common in primary grades, dual-language classrooms can exist as separate sections within traditional schools, or as part of dual-language campuses.

Teachers here rely on strategies such as cooperative learning and the whole-language approach to equalize the class experience. Lessons are bolstered with hands-on activities and role-playing games, requiring students from different language backgrounds to work together and allowing language learners to use prior knowledge in ways that don't require fluency.

"I didn't know any English when I came here," explains Fratney third-grader Dariana. Now she sits at a cafeteria table with a mix of native Spanish- and English-speakers, and they talk in a blur of two languages. "I feel like I learn faster, because they help me with English, and I can help them with Spanish."

With its comprehensive approach to dual-language education, Fratney could be seen as a model of social inclusion — yet its lessons can be applied to classrooms anywhere.

Seattle's Cedar Valley Community School took on a social inclusion approach when a rapid growth in ELL students made it clear that the old pull-out approach to ELL instruction wasn't working. Cedar Valley was mostly English-dominant a decade ago: now 40 percent of the students are ELLs.

"We knew that students spent most of their time in mainstream classrooms," says ELL teacher Ellen Riggs. "If mainstream teachers could modify their classroom instruction to meet the needs of ELL students, that would benefit everyone."

Two basic components were missing: Spanish-language reading materials and staff who spoke Spanish. With the help of a grant, Cedar Valley faculty purchased bilingual class readers, selected by teachers for use in classroom instruction. They also bought Spanish-language books that kids would read for pleasure.

"If they can carry around a Spanish version of Harry Potter, it enables them to feel like they're part of this culture and this school community," says librarian Stephanie Smith.

A second grant funded Spanish classes for staff. Teachers learned school-specific phrases, such as how to ask a student if she needs to go to the nurse, or how to greet students on the first day of school.

"I thought our staff would benefit from being in the role of the language learner— [learning] what it felt like to struggle with a new language, to feel hesitant to speak up," Riggs says.

Outside the Walls

Silverado High School in Las Vegas, Nev., uses a different approach to social inclusion — taking it outside the classroom, and sometimes completely outside the schoolhouse.

The approach worked for Bandana Paija, originally from Nepal, who moved here three years ago at age 15.

"I was really anxious and thought I might not fit in," Bandana says. From the open campus to the passing periods to the lack of other Nepalese students, she says, "everything was so different."

Then she learned about an after-school club called GlobaLab, co-organized by her ELL teacher, Yvonne Caples. GlobaLab pairs English- and non-English-speaking students in activities structured around cultural and science-related themes.

"It was hard for (ELL students) to be involved in many things during the regular school day, because they had so much to make up," Caples says. GlobaLab gave ELLs the chance "to interact with mainstream students, so they could feel like they had something to contribute."

Each year, members tackle human rights and environmental topics through a series of research projects. Bandana and her peers chose refugee issues and water quality.

Over spring break, GlobaLab members embarked on a five-day field trip to California's Mono Lake, where they joined high school students from Modesto, Calif. The Silverado students represented 10 countries and multiple languages, including a few native English speakers; the Modesto kids spoke only English.

At first, says Bandana, "I thought the English-speaking students were going to laugh at my accent. I was worried and scared to speak up in front of them."

When group leaders invited questions, only Modesto students answered. So Caples pulled her students aside. In a small group, they brainstormed questions, then invited instructors to join them. Asking their questions in a smaller, more structured environment gave them the practice they needed to feel comfortable interacting with the larger group.

"It opened the floodgates," Caples says. "They started asking all sorts of questions. And soon, we saw (the Modesto students) open up to the ELL students, joking with them and treating them just like any other student."

By the end of the trip, Bandana had exchanged email addresses with a student from Modesto. "They didn't laugh at us," she says, "they helped us!"

After the trip, Caples noticed GlobaLab members were more likely to speak out in mainstream classes, compared to ELL students who weren't part of GlobaLab. In addition, they were more comfortable speaking English, even with other students who spoke their native language.

Embracing "Otherness"

Riggs, of Cedar Valley, enjoys watching her English-dominant students develop friendships with ELL peers. Along the way, she says, the English-dominant kids pick up Spanish vocabulary without formal study, which gives them a leg up if they choose to study Spanish in secondary school.

Just as social inclusion helps ELL students learn the culture of their new community, inclusion exposes all students, including native English speakers, to "multiple ways of thinking, solving problems, and living in this world," Riggs says. "When so many problems of late seem to be the result of not knowing each other and not listening to one another, the social inclusion of ELL students seems an obvious route to embracing 'otherness.'"

0 COMMENTS