“Wish for the best; expect the worst.”

That’s the mantra of girls in the juvenile justice system, says Liliana Gaitan, a young woman who entered the system at the age of 12. She says it’s “a reminder to us we aren’t handed the best things in life, and rather than try to figure out why, we expect it.”

Gaitan is one of the growing number of young women who have been funneled into U.S. juvenile detention halls and then ultimately on to the adult justice system. According to the National Council on Crime and Delinquency’s (NCCD) Center for Girls and Young Women, girls now account for 30 percent of juvenile arrests and 15 percent of juvenile incarceration—making them the fastest-growing demographic in the juvenile justice system.

What’s worse, girls often fail to receive the support they need in school, while in the system and after they are released. This happens because girls still make up a relatively small portion of the general juvenile justice system population and because they are still perceived in schools as being at less risk than their male counterparts, which is partially due to the important—but often gender-limited—light currently being shone on the school-to-prison pipeline.

Educators have an essential role to play in righting this situation, primarily through gender-responsive education strategies that address the specific needs of at-risk girls.

Who Is “At Risk”?

Understanding which girls are at risk and what their specific needs are can be complex, says Gabriela Delgado, who oversees the Gender Responsive Services unit at the San Diego County Office of Education. For her, the first step is asking the girls themselves. “They may not always articulate their needs the way we would,” says Delgado, “but if you listen, the information is there.”

Gaitan could have benefited from this kind of personal interest. She remembers her childhood as one of apprehension, trauma and avoidance. “I recall being young and going to school worried that we would end up having no house,” she says. “My mother was always worried about how we were going to pay the rent.” She avoided her classmates and teachers, hiding in the restroom during recess and breaks between classes. Eventually she began using drugs.

Asking the right questions is necessary, but it’s also important for educators to understand the big picture. According to the NCCD, 70 percent of girls in the juvenile justice system have been exposed to trauma; 60 to 80 percent need substance abuse treatment. And three out of four detained girls receive mental health disorder diagnoses.

The Tipping Point

After confiding in a middle school counselor that she had been sexually abused by an uncle and was cutting herself, Gaitan was briefly placed in an out-of-home treatment facility. Disillusioned with the support her school could provide and determined to protect herself, she began carrying a knife. When police stopped her and a friend for smoking marijuana and found the knife, she was arrested and taken to a juvenile justice facility.

“I remember so many emotions running through my head,” says Gaitan. “I was scared of what might happen. ... I felt like a bad person for always making my mom cry. ... At the same time, however, I was excited since I had heard about juvenile hall before and knew kids who went there were looked at with respect.”

No school will have the perfect support system for every individual girl’s needs. That’s no excuse for giving up.

Gaitan’s story is not an uncommon one—many girls’ first experiences in the justice system are initiated by nonviolent offenses. “A lot of girls living with scrutiny and self-doubt are not necessarily performing well, are often outspoken,” says Monique Morris, co-founder of the National Black Women’s Justice Institute, “and it often conflicts with what society expects ‘good girls’ to be doing.” When those societal expectations play out in the juvenile justice system, it results in harsher prosecution for less-serious offenses for girls than boys, according to research by the NCCD.

These societal definitions of “appropriate behavior” are often applied even more heavily to girls of color because of cultural disconnects between them and authority figures. In her research, Morris found that black girls report being reprimanded for being “loud” and “defiant” when they felt they were simply expressing themselves naturally. “These girls may react to conditions around them in ways that many educators are not able to handle so well because they see it as an affront to their authority,” says Morris. “When [girls] step forward and want to engage critically, depending on how they represent femininity, they’re sometimes removed from the classroom all together.”

A Continuum of Care

Most educators aren’t in a position to directly affect what girls are experiencing inside the walls of juvenile detention halls, but providing prevention and transition support can mean the difference between a girl entering a cycle of incarceration and poverty or escaping the system—as Gaitan did when she was 19.

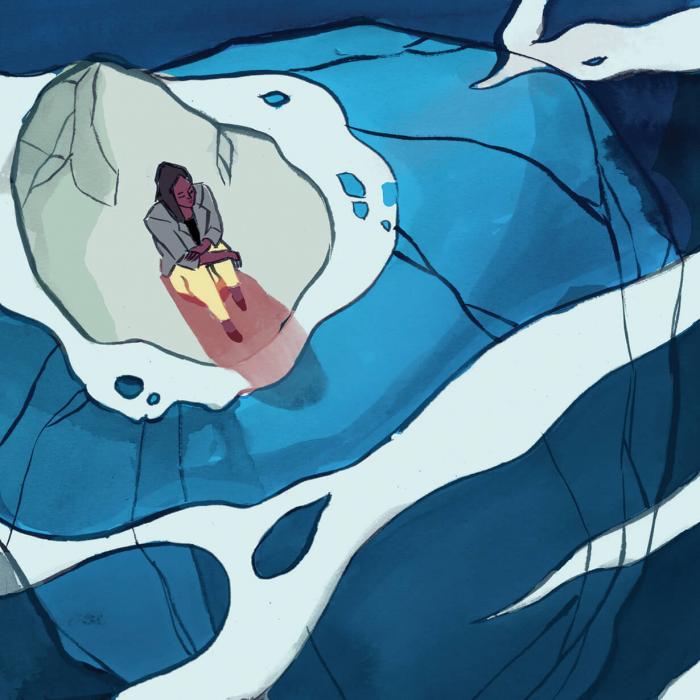

Delgado uses the analogy of an iceberg to explain the experiences of girls like Gaitan. “You really see the tip, but underneath the water level, there is a massive amount of ice. If you take that and apply it to a kid’s life, on the surface level you’ll see destructive behavior and thought processes, truancy and low self-esteem,” she says, “but in order for her to feel whole again and for us to work with her effectively, we have to see what’s underneath it all—the trauma, abuse, not feeling connected to people.”

According to both Delgado and Morris, that lack of connection is one of the first challenges individual educators need to face. “The important thing is to construct a learning environment that has a foundation of trust,” says Morris. “A lot of these kids aren’t engaged in materials because they don’t see themselves in them.”

Creating culturally inclusive classrooms that respect girls’ diverse methods of engaging can change that, says Morris. “There are many ways in which classes are reproducing society’s norms, and part of what educators can do is to actively engage these norms and then actively disrupt them.”

That disruption is no small task—and it’s not one that can be accomplished solely in individual classrooms. “There shouldn’t be just one person supporting gender-responsive groups,” says Delgado. “The whole school staff should be building that school climate.”

She calls it a continuum of care, and it includes facets as diverse as anti-bullying policies that include specific language addressing covert bullying (also known as relational aggression) to regular professional development on gender-responsive education strategies.

She also emphasizes the need for wrap-around services. The first thing an educator should ask herself, says Delgado, is “Are we properly assessing this student? Did someone meet with her one-on-one? Did someone who knows her well meet with her?”

These questions are even more important for students re-entering school after time in the juvenile justice system. Those girls need the support of many people, Delgado says. “It’s not just one agency; it’s multiple agencies. That requires communication to make sure no one falls through the cracks.”

Even in the best of circumstances, the harsh reality is that no school will have the perfect support system for every individual girl’s needs. That’s no excuse for giving up, though, Delgado emphasizes. “There may not be a perfect fit, and that’s hard for us counselors or teachers because you want it to be the best thing, but the reality is you may not have exactly what you want. You have to ask yourself, ‘Within the context of what I have, what can I offer her that will be meaningful for her?’”

The Nuts and Bolts of Gender-Responsive Education

Gabriela Delgado (who leads San Diego County’s Gender Responsive Services unit) offers some concrete and immediately implementable strategies for becoming a more gender-responsive educator.

Know Her Name

Calling a girl by her first name is powerful, says Delgado. “It tells her you see her, that she’s worth remembering.” And for girls coming out of the system, it’s especially important—institution staff often call girls by their last names only.

Be Yourself

Being genuine creates trust. Kids need to see that you’re not perfect, says Delgado, “that you don’t have it all figured out and that along the way you too were looking for guidance. Girls aren’t looking for someone who has the exact same experiences as them. They’re looking for someone they can trust.”

Provide Role Models

Whether you invite guest speakers or create a Wall of Influential Women, “girls need to see that there are women who have laid down a path, and we can probably learn a thing or two from them,” says Delgado.

Ask About Content

Let girls tell you what they want to learn. Once you know what they’re interested in, you can begin to build lessons and curricula that meet their needs.

Bring Girls Together

Sometimes schools separate girls into groups based on ethnicity, risk level or other factors. But allowing girls of all backgrounds to share experiences and empower each other can be even more effective.

0 COMMENTS