For Trinity Thompson, the decision of whether or not to address high-profile killings of Black people with her second-graders was a no-brainer. She was teaching in Harlem soon after Eric Garner was killed by a police officer in a nearby New York City borough.

“How do I respond to this?” Thompson recalls asking herself. “And then from there, it was like, How do I respond to this—again?” Each time news reports covered another Black person dying at the hands of police, her students—most of whom were Black—asked more and more difficult questions. A career-long social justice educator, Thompson was committed to a response that focused not only on the problem, but also on how people were resisting it and seeking solutions.

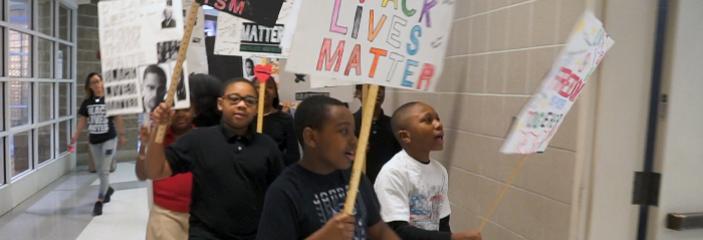

And that meant teaching second-graders about Black Lives Matter (BLM).

She knew it was risky. When the Black Lives Matter movement comes up in conversation, it is often characterized in one of two ways: as the work of strategic activists drawing attention to and combating issues that harm Black people, Black communities and humanity at large, or as a movement marked by violent outbursts and driven by an exclusionary, racist, anti-police agenda.

This split gives some educators pause when it comes to teaching about BLM. Others embrace the topic, recognizing it as an opportunity to teach about collective action and to link past racial justice movements to the present. But all educators, by virtue of the fact that their students have either direct or mediated exposure to Black Lives Matter, should know the basic facts about the movement’s central beliefs and practices.

Not all of us are like Thompson; the students who sit in front of us daily are not always directly affected by the killing of unarmed Black people or any of the other injustices that plague our nation. But as teachers who function as caretakers, truth-seekers and advocates of justice, we can acknowledge how the threat of justice in one community is, to borrow from Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., a threat to justice in every community. We have a civic responsibility to be educated about Black Lives Matter and, as we learn, we must teach.

The Beginning and the Hashtag

The Black Lives Matter movement began with a commitment to ending police brutality and state-sanctioned violence and injustice against Black people. It is also dedicated to affirming Black people’s “contributions to this society, our humanity, and our resilience in the face of deadly oppression,” according to its founders. The movement was started by three Black women—Alicia Garza, Patrisse Cullors and Opal Tometi—following the 2013 acquittal of George Zimmerman, a Florida man who had shot and killed Trayvon Martin, an unarmed Black teenager, the preceding year. Garza took to social media the night of that acquittal, stating in part, “Black people. I love you. I love us. Our lives matter.” A year later, Michael Brown, another unarmed Black teenager, was shot and killed by a white police officer in Ferguson, Missouri; the officer was not indicted. Shortly thereafter, the internet was filled with messages of outcry and support that included #BlackLivesMatter.

Since the Ferguson action in 2014, BLM has taken shape as a multichapter national organization; 37 chapters currently operate in the United States, one in Canada. Many BLM chapters and other organizations that embrace the movement mobilize people to demonstrate in communities where police shootings have occurred and to convene at large gatherings—such as political rallies—to bring awareness to police brutality. The website of the original group, blacklivesmatter.com, also lists other types of local and national events, such as teach-ins, panels and Twitter chats, and encourages organizers to submit their own events.

In an October 2016 interview with TEDWomen, Cullors explained what the movement means to her.

“Black Lives Matter is our call to action. It is a tool to a reimagined world where Black people are free to exist, free to live. It is a tool for our allies to show up differently for us,” she said. “I grew up in a neighborhood that was heavily policed. I witnessed my brothers and my siblings continuously stopped and frisked by law enforcement. I remember my home being raided. And one of the questions, as a child, I had was why? Why us? Black Lives Matter offers answers to the why.”

Myths and Criticisms

People who don’t follow Black Lives Matter usually become aware of the movement when news sites report on BLM actions or protests. What many people don’t realize is that the leadership also embraces policy change and legislation as necessary elements to end oppression of Black people—and that the work and the leadership are not limited to the Black Lives Matter network.

One common misconception about the BLM movement is that it is leaderless. But there isn’t one leader; there are many. “BLM is composed of many local leaders and many local organizations including Black Youth Project 100, the Dream Defenders, the Organization for Black Struggle, Hands Up United, Millennial Activists United, and the Black Lives Matter national network,” organizers explain on the website. “We demonstrate through this model that the movement is bigger than any one person.”

Another misconception is that the movement is solely a mechanism for protest. In fact, the many people and organizations with agendas and goals that overlap and align with BLM have produced detailed policy demands and proposals for institutional reforms. Campaign Zero, for example, outlines a list of policy proposals largely focused on ending police brutality. It is a strategy for addressing one of the most visible, damaging and deadly symptoms of systemic racism. The Movement for Black Lives, a collective of more than 50 organizations, advances a platform covering six areas of domestic-policy reform, including economic justice and investment in equitable education and health care instead of criminalization and incarceration.

Many people, however, view the BLM movement as violent, seeking to “sow a racial divide” and intent on interrupting the work of police officers commissioned to protect and serve the public. For example, Rudy Giuliani, the former mayor of New York City, said in a television interview that the movement is “inherently racist” and “divides us.” He further stated, “They don’t mean ‘Black lives matter’; they mean ‘let’s agitate against the police matters.’”

This movement is not your grandmama’s civil rights movement; it is the movement of her children’s children, more specifically her daughters.

Another common criticism of the movement is that it should be more like the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s, which is praised today as a seemingly perfectly orchestrated and acceptable movement. Some critics who prefer the style and tactics of that movement find it difficult to imagine that the BLM movement might actually be an extension of the work that was done in the 1950s and ’60s.

Still, perhaps the gravest criticism and misunderstanding of the BLM movement—and every movement for freedom, from slave rebellions, abolitionist movements and the Underground Railroad to Black Liberation Movements of the 1960s and ’70s—stems from a failure to acknowledge the conditions that created the resistance.

In a speech given at the 2016 BET Awards, activist and actor Jesse Williams addressed this disconnection: “If you have a critique for the resistance, for our resistance, then you better have an established record of critique of our oppression.” Without an understanding of the ever-present effects of slavery and the systems that have been built to protect and preserve the devaluing and oppression of Black bodies, BLM—and any other movement for rights concerning people of color in this country—will never be understood.

However, a host of resources exists that explain systems such as mass incarceration, police brutality and economic and educational inequality. These resources all point to a larger system that is not necessarily broken, but functions the way it was designed to: to oppress the very people who were originally brought to the United States as chattel. The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness by Michelle Alexander, Are Prisons Obsolete? by Angela Davis, Assata by Assata Shakur, Between the World and Me by Ta-Nehisi Coates, and Ava DuVernay’s documentary 13th are a few of the many resources that provide context for the types of resistance that exist today.

This context is necessary to understand why, in 2017, the movement is called Black Lives Matter—because, historically, Black lives have not mattered.

Not Your Grandmama’s Civil Rights Movement

“People like to romanticize the civil rights movement,” says Professor Duchess Harris, who teaches in and chairs the American studies department at Macalester College in Saint Paul, Minnesota. “They like to say that it was more organized, it was more productive, and that America was more open to it than Black Lives Matter. That is quantitatively not true.” Harris, who co-authored a Black Lives Matter textbook, cites research showing that, in the 1960s, the majority of Americans did not approve of even nonviolent tactics, such as passive resistance. “When the civil rights movement was actually going, it was denounced,” Harris clarifies. “Now that we have distance from it, people celebrate it. It was not celebrated in the ’60s at all.”

The same criticisms being leveled against the leaders of Black Lives Matter, Harris says, were leveled against Dr. King, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and other civil rights activists and groups: that the protesters cause unrest, don’t respect authority and do more harm than good by taking to the streets and causing problems. Noting such similarities can help contextualize much of the negative rhetoric that surrounds Black Lives Matter.

If you have a critique for the resistance, for our resistance, then you better have an established record of critique of our oppression.

But it’s also important to note similarities in the work and philosophies of the two movements. In addition to calling for policy and legislative changes (civil rights work led to the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965), emphasizing the humanity of Black people and acting collectively, along with white allies, is common to both movements.

However, BLM bears some noteworthy distinctions from the civil rights movement, namely the acknowledgment of women (particularly as leaders), the decentralization of power and the fact that BLM’s women leaders self-identify as queer. This movement is not your grandmama’s civil rights movement; it is the movement of her children’s children, more specifically her daughters. The leadership of the civil rights movement often silenced its women leaders, such as Fannie Lou Hamer, Dorothy Height, Diane Nash, Recy Taylor and countless other women whose names and sacrifices are still largely unknown. It was also heterosexist, keeping key leaders who were openly gay, such as Bayard Rustin, behind the scenes.

The strategies and tactics of social movements are rooted in their times, so it is no coincidence that the leadership of this generation looks different and is carried out differently from the civil rights era. No longer is there a stark concern for the politics of respectability that in some ways stymied the activism of the 1950s and ’60s. And while the Black church was and still is committed to advancing the rights of people of color, BLM activism boasts a great range of diversity that includes Christians, Muslims, atheists and people of all religious and nonreligious beliefs. There are no rules that will indirectly or directly keep certain groups from participating in this movement. Additionally, the use of technology, particularly social media, has equipped the BLM movement with capabilities that allow “regular” people to be “citizen journalists.” #BlackLivesMatter has become a tool used for mobilization.

This movement for rights and humanity is growing by the day and is bolstered by the very technology young people are using. Our students need to know the facts about BLM’s role in this historical moment and how it connects with a history of social change.

*This article was revised 1/24/2022 to capitalize the words Black and Brown.

But Don’t “All Lives Matter”?

Perhaps the most common criticism leveled against the Black Lives Matter movement is that the movement is racist because it focuses on Black people. One way to counter this notion is to point out that all lives cannot matter if Black lives do not, and to educate the critic about the conditions that ignited the resistance. Another is to emphasize that Black Lives Matter is rooted in the deeply humanistic belief that all lives are connected. All oppression—including that of LGBT individuals, refugees, immigrants, Muslims, women, people living in poverty and people with disabilities—negatively affects all lives. Although the BLM movement focuses on the oppression of Black people, its mission is intersectional and invested in liberation for all.

0 COMMENTS