Just a few weeks after River Ridge High School approved the new Black student union (BSU) as an official club, a few members came into a meeting with something to share: a flier advertising a white student union at the school. The club for white students would turn out to be a prank, but it was precisely the type of rhetoric that had inspired them to start the BSU in the first place.

Several months earlier, students had approached art teacher Christie Tran with fear and anxiety in the wake of the divisive 2016 campaign. Already used to gathering in her room—“all the time, before school, after school, during lunches,” she recalls—they had built a rapport of trust together. They shared their thoughts openly with her, their fears that the campaign’s rhetoric was inciting more violence toward black and brown people. With heavy hearts, they wanted to take collective action.

River Ridge is located in Lacey, Washington. Just under 7 percent of the school’s students are Black, and 74 percent of Lacey residents are white. Consequently, Black students do not get to see a lot of representation at school. The students who gathered in Tran’s room had a problem with this. They knew Tran had co-founded the school’s multicultural club, so they asked if she wanted to collaborate. She agreed, and after a few months, they decided to form a Black student union.

Then-sophomore Drayden Alexander was tapped to draft the BSU’s first constitution. Alexander, who has ADHD, says writing this document was the most focused effort he had ever put into anything in his entire life. He attributes his drive to an innate desire to lead: “I want to make a difference in my community,” he says. “I want to be somebody in the history of the race who did something important.”

The group’s constitution outlines its mission and philosophy, which features five key pillars: education, outreach, representation, civic engagement and economic empowerment.

Education First and Foremost

Tran says students began by expressing a strong desire to learn more about their own histories, cultures and communities. “It goes back to honoring these kids,” she reflects. “We wanted to teach it in a way that honors [students] and doesn’t make them ashamed or embarrassed about their history.”

When students sought out additional education on Black culture and history, Tran applied for and received a Teaching Tolerance Educator Grant. The club used the funds to buy resources like book sets and films and to go on field trips and bring in guest speakers. During club meetings, they held breakout sessions to discuss various cultural issues. For example, they explored the meaning behind the mantra “Black is beautiful” and the Afro-futuristic world of Wakanda, Black Panther’s imagined African nation unencumbered by a colonial past.

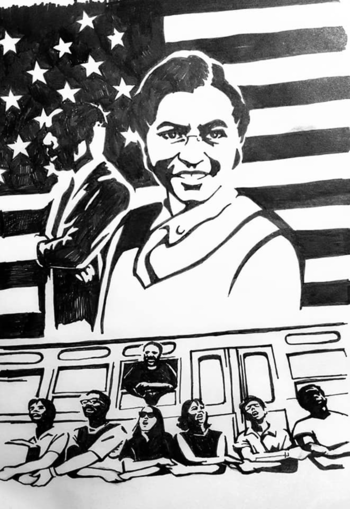

Jawanne Brown, who—with Tran and paraeducator Gabby Wade—serves as one of the club’s advisors, says the BSU’s educational component instills a sense of pride in the students’ culture. He points out that they’re learning the histories of “great, powerful African Americans who have impacted the world.”

Interested in applying for an Educator Grant?

Learn more here!

Outreach as Representation

But learning doesn’t just focus on the past. Students also used meeting time to discuss the “Pygmalion effect”: the theory that a teacher’s expectations of a student significantly influence the student’s academic future. Education literature, they learned, posits that teachers of color tend to perceive students of color—and all students—more positively than other teachers.

According to the 2017 report “The Long-Run Impacts of Same-Race Teachers,” having just one Black teacher in elementary school cuts high school dropout rates by 39 percent.

Following these conversations, BSU students resolved to mentor their younger peers. Tran remembers, “[My students] said if they had seen more teachers of color, adults of color, older students of color in the classroom, it would’ve been a different experience at school for them.”

When the local elementary schools heard about the club, the BSU began getting requests to speak at assemblies honoring Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Excited to serve as mentors, members even donated their own hand-drawn portraits of prominent Black historical figures to the elementary school they partner with most often.

Engaging the Community

The BSU’s engagement didn’t end there. Another way the group fosters Black representation and community is by patronizing Black-owned businesses. And they’ve formed a business of their own.

It’s been really powerful for our kids to have a voice so they’re not just high school kids feeling out of place. They have a purpose. They have a home.

When the BSU first created its constitution, Tran knew the club would need funding. She worked with students, supporting them as they built their graphic design skills. Now, the BSU runs a print shop. Students fill orders district-wide for “Black Lives Matter” hoodies and shirts featuring their artwork. BSU students manage the ins and outs of the business—from monitoring profits to maintaining inventory and depositing funds after events. Several are planning to pursue business careers.

It’s All About Empowerment

BSU members maintain a packed schedule. They are currently petitioning the district to mandate ethnic studies courses and advocating for more robust restorative practices to disrupt the school-to-prison pipeline. They have addressed equity committees at district schools, the multicultural action committee, a minority educator roundtable and several state senators’ meetings.

They’ve even worked on pushing educators beyond a cursory engagement with Black History Month. “We talked to the school board about changing the curriculum to teach less about slaves and more about Black history,” recollects Drayden Alexander, author of the group’s constitution. He reports that they are working toward more diversified curriculum as a result.

That’s not to say everything’s gone smoothly for BSU members. The club initially faced pushback. Some students and community members thought the club’s focus was exclusionary. But Alexander maintains that its intention was always empowerment.

“A lot of people think that because we’re saying, ‘Black lives matter,’ we’re saying Black lives matter only, or they think we don’t want to include other people,” he explains. “Because we call it the Black student union, people think only Black people can be part of it, but we never said that. In fact, we said just the opposite.”

River Ridge’s administration offered support in the face of the pushback, fielding calls from families and community members about the nature of the club. The backlash has since quieted down, and even the “white student union” incident was seen as an opportunity for growth.

“There was a restorative circle conducted with the two kids who orchestrated the whole thing,” remembers Tran. “They were freshmen, they were goofing around; they just didn’t understand the impact of their joke. BSU explained how hurtful it was to them, that this was their passion and not something to be made fun of.”

The students in the BSU continue to be agents of change. At this year’s Martin Luther King Jr. assembly, the BSU persuaded school leaders to open up the conversation about social justice. Students opted to move away from a “sugar-coated, black-and-white history of the civil rights movement,” says Tran, and toward a celebration of the diverse populations that have made grassroots contributions to civil rights. BSU students invited students from other affinity groups—including the Gay Straight Alliance, clubs for Latinx and First Nations students, and others—to present speeches envisioning a world where they felt fully embraced and empowered.

BSU members draw on the support of their advisors to help build that world. They seek out Wade for advice, or they casually gather in Tran’s or Brown’s room to plan events, discuss the news or seek out each other’s ideas.

“Being in a community like this can be hard for students of color,” Brown notes. “It’s been really powerful for our kids to have a voice so they’re not just high school kids feeling out of place. They have a purpose. They have a home.”

Ehrenhalt is the school programs coordinator for Teaching Tolerance.

0 COMMENTS