"So few take the time to sofu,” says the young woman in the center of the screen. “Speak out for understanding. Open your mind. Raise your eyes to the unveiling of the face behind the mask, the crumbling of the stereotype. A collective journey. Our journey.”

It’s an awkward moment. Viewers wonder: What does "sofu" mean? Why does this woman talk about it in such an impassioned way? And what am I supposed to “open my mind” to?

That’s exactly what you’re supposed to think. Welcome to Speak Out for Understanding, a new film on learning disabilities created by a group of students at a Vermont high school. Made on a shoestring, the award-winning 32-minute documentary overturns a number of popular assumptions about learning disabilities — and tries to teach a new way of talking about the people who have them.

The film gives viewers a close look at the real lives of four students who have learning disabilities. We see Tucker Sargent shredding on a snowboard; Tanner Skilton acing a downhill slalom course; Grace Kirpan showing off her cross-country running medals; and Emma Wade playing saxophone in the school’s jazz band.

We also hear Tucker describing life with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder; Tanner talking about the world as seen by a person with dyslexia; Grace and her mom discussing their experiences with Down syndrome; and Emma explaining how she knew “something was wrong” even before she was diagnosed with specific learning disabilities.

And we hear, in their own words, how students feel about the labels applied to people with disabilities.

“I don’t have a problem standing up for who I am,” says Emma. “I’d rather do that than conform.”

Their Own Stories

When they step out as public advocates for their rights, people with learning disabilities often find themselves facing an uphill battle.

Educators have known for some time that it’s important to use “people first” language – using terms like “children with dyslexia” instead of “dyslexics.” In the popular media, however, it’s often the disability that is mentioned first. Most newspapers still use the blanket term “the disabled,” which some people with disabilities find confining.

More importantly, it’s often “experts” who are doing the talking in the media, rather than people with disabilities themselves. The focus is usually about the challenges and the struggles people with disabilities face – not their skills and talents. Sadly, many people still use “retarded” as an insult, or casually joke about having attention deficit disorder.

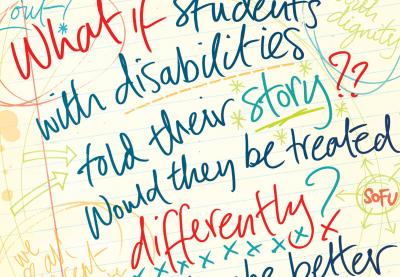

In September 2007, speech pathologist Maureen Charron-Shea sat down with a group of students at Harwood Union High School in Moretown, Vt., where she teaches. Some of the students in her group had learning disabilities, and some did not. Charron-Shea asked them all the same question: “What if students with disabilities told their own stories? Would they be treated differently? Would they be better understood?”

The students took it from there. They proposed making a documentary film, using members of their own group as subjects of the documentary. At first, Charron-Shea didn’t realize the scope of their ambition.

“I didn’t know what I was getting into at the time,” she says. “I thought, ‘well, maybe we’ll make a little five-minute film on my laptop or something.’”

Instead, she says, “the idea and the vision grew and grew.”

Students spent an entire school year working on the project. They gave up lunch hours and study halls, and even came in after school to work on the film.

“Occasionally we did something called an in-school field trip, where students got permission to be released from their classes for a half-day or a whole day [researching and filming] in the library,” Charron-Shea says. “The teachers and administrators of the school were very supportive.”

The young filmmakers went out into the hallways of their school, to ask fellow students and teachers what they know about learning disabilities. And then they turned the cameras on themselves, exploring their own journeys toward an understanding that being different just means that you’re… well, different.

“We see and hear and do things in our own way,” Tanner says in the film.

‘I Didn't Know Who I Was’

In the film, Tanner talks about his struggle for access to the same opportunities available to other students.

“I have dyslexia, so they wanted me to work on my English skills, on my grammar and my punctuation and all those other things, instead of French or instead of going to a library class or an art class,” Tanner said. “I had to do other things.”

Tanner says he gets frustrated about the beliefs people sometimes have about dyslexia. “I’ve looked it up on the Internet, and it’s usually defined as ‘difficulty reading and writing,” he said. “That’s not all. That’s part of it.”

For Tanner, having dyslexia means working a lot harder in some classes, devoting more time to his studies, and realizing that this situation will always be with him. But he doesn’t consider himself “disabled” and he notes that his way of processing information can be a good thing.

“We do and see and hear things in our own way,” he said.

Emma talks about the self-discipline her schoolwork requires of her: the extra hours of study, the work after school and in study hall and her constant struggle with her own perfectionism. Emma’s disability falls into the category of specific learning disabilities, or SLD – a broad category that includes a number of difficulties with fluency and auditory processing.

“I want to be able to get the work done,” Emma says. “There’s a certain quality that I have to reach, and if I can’t do that, then that’s very frustrating.”

Tucker talks about his days as a “troublemaker” in elementary school, where he had trouble fitting in because of his attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Tucker says he compensated by doing risky things and taking dares.

“I really didn’t know who I was,” he said.

Like all the students in the film, Tucker has come to terms with life in a school system where he is labeled as different from the “norm.”

“It’s used to categorize people, and it’s saying ‘oh, that person has a disability,” says Tucker. “Everybody has their own disability.”

The Other Side

For Greg Sharrow, education director for the Vermont Folklife Center who worked with the students on the film, getting to this place of self-acceptance is the real point of the whole film project.

“One of the things that happened through this storytelling process was that we kind of got through to the other side,” Sharrow said. “[We arrived] at a point in each of these young people’s narratives where essentially they were talking about having achieved a sense of wholeness.”

The interview process wasn’t just about collecting information, Sharrow said. It was about helping students develop their own stories “until they arrived at a place of strength,” he said.

“I’ve found that if you give children the language to talk about their learning and their challenges, then it’s no longer so shameful; it’s just the way it is,” Sharrow said.

Perhaps not surprisingly, the students’ new sense of self also leads them to speak out. Students with disabilities often live in a world of acronyms – ADD, IEP and so on. In their film, the Harwood students try to introduce their own acronym. The word “sofu” stands for “speak out for understanding,” and the students urge viewers to do just that.

That advocacy pleases Charron-Shea. She notes that students with learning disabilities usually have Individualized Education Plans (IEP) that emphasize self-advocacy and an understanding of one’s own learning style. The film project addressed those topics head-on.

Just as importantly, she says, the film project helped students develop a wide range of research skills and understandings about human rights, civil rights and social justice.

Speak Out for Understanding has developed a following outside the halls of Harwood Union High School. After the film’s premiere at the school, Vermont Public Television picked up the story, broadcasting clips of the film and a group interview with the students. Soon, Charron-Shea was getting requests for copies of the film from teachers across the country. The project also caught the eye of the National Youth Leadership Council, which gave the project its 2009 Youth Leadership for Service-Learning Award.

Still, the best feedback has come from places much closer to home. At Harwood’s commencement ceremony, a mother approached Charron-Shea and thanked her for the project, saying her son’s participation in the film caused him to develop a real sense of caring for the people around him. “She said ‘He’s a different person now,’” Charron-Shea recalls. “And I just about started crying.”

Charron-Shea’s students are now finding new creative ways — like rap, wikis and visual art — to get out their message. Also in the works is a children’s book that Charron-Shea’s students hope to share with younger children to encourage self-reflection and discovery of their own abilities.

Charron-Shea is happy that the film has found a wide audience, but she would much rather see schools doing similar work on their own.

“I’d like to see this project replicated because it is so powerful,” she said. “It’s the process, not the product. What’s more powerful than engaging your own community in a conversation?”

Rhonda Thomason contributed to this piece.