Hannah Paredes, 14, never thought that she’d fall in love with history by cleaning a grave. She didn’t know much about Vietnam War heroes either, and the name Milton A. Ross was meaningless.

But it all came alive when she participated in the Omaha Public Schools’ “Making Invisible Histories Visible” program, or MIHV. Omaha’s schools have a low failure rate among 8th graders but a high one among high school freshmen. MIHV was created to help at-risk students “adjust to the increased demands of high school,” says Emily Brush, the project’s coordinator.

Hannah is one of the 9th graders who have taken part in this seven-day camp held every summer since 2010. By working alongside teachers and mentors, the program’s 44 students bring history to life by discovering the hidden stories of North Omaha’s African-American neighborhood. Students spend time there talking with people. They also work with archival material and collect oral histories. Their goal is to piece together the community’s often invisible history.

Harris Payne, director of MIHV and supervisor of social studies for Omaha schools, says that one of the goals of the project is to create a powerful connection between the students and the subjects they are studying. The philosophy is “get the students outside and have them experience the world,” Payne says. “That’s a very powerful teaching moment that the students will not likely forget.”

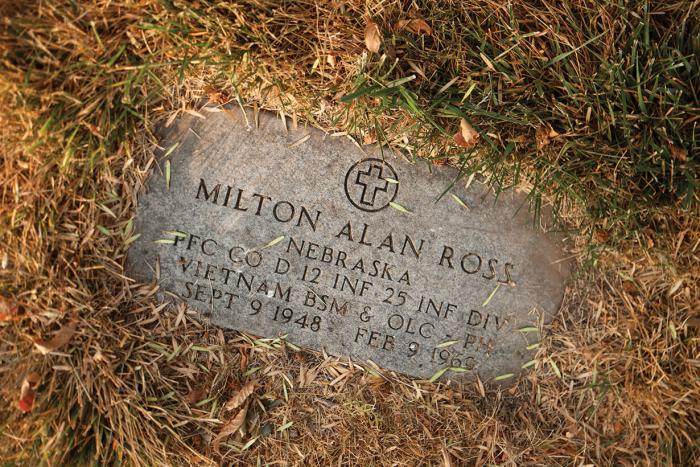

A Neglected Hero

During her research, Hannah learned that Milton A. Ross was a decorated African-American soldier who died in Vietnam. Hannah and her teammates also discovered that this war hero’s grave was overgrown and untended, a situation that they rectified with some garden tools and flowers. “MIHV made history come alive—it’s no longer just a boring textbook,” she says. “And it was kind of a wake-up call for me to do better in school.”

Having at-risk students experience history first-hand is the key to increasing motivation and the reason for creating the program. Students involved achieved a statistically significant improvement in their knowledge of history and their ability to use online technologies. The program also gave teachers a better grasp about how to teach African-American history. “I used to hate school,” Hannah says, “and after participating in the program, I love it.”

Other students who took part in MIHV agreed. Mckenzie Clayton, 14, worked on a story about Omaha’s African-American newspapers. She says that the program improved her writing, research and critical-thinking skills as well as her social skills. She also learned a great deal about her own personal history by doing practice interviews with family members. Ronnie Turner, 16, now a junior at Burke High School in Omaha, says, “The program really affected my ability to research using my community as a tool for learning.”

The students created a digital archive of their work (ops.org/invisiblehistory) that is broken into 16 wide-ranging topics including civil rights, music, sports, work and church. Part of the idea behind MIHV was to close a gap in local African-American history, says Payne. “We live in a multicultural country, and we wanted the kids to see themselves in what they learn.”

Brush emphasizes how MIHV animated North Omaha, a neighborhood that has been stigmatized for being predominantly African-American. News reports about the area often focus on negative aspects such as crime or poverty. “MIHV brought a new, positive light to [the community] through the student’s dedication to tell the untold,” says Brush.

Spreading the Success

Other school districts that want to emulate this program need to work closely with the community beforehand, discussing the vision of the project. Payne says that it’s important to develop an action plan that includes goals and how they will be measured, capital and human resources, and what the end product will look like. “Our staff consists of teachers, graduate students, historians, a project director and an administrator,” he says. “Each has a specific role to plan and each has a unique contribution to the project.”

The biggest challenge is getting people in the community and the school to buy into the vision of a project that gets beyond the superficial aspects of history. “We use the example of postcards as a tool to communicate what we are trying to do,” Brush says. “You see postcards in every city, but how often do they truly reflect the racial and ethnic makeup of that city?”

Teachers who participated in MIHV say that it helped students—and themselves—discover new ways to relate to their community and their history, going beyond what’s normally taught, such as Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X. “The biggest thing I got out of the project was an appreciation for revealing histories that haven’t been traditionally taught,” says Nicholas Wennstedt, a history teacher at Bryan High School in Bellevue, Neb. “I’ve carried this lesson over into all the classes I teach.”

Teachers also say that there’s no mistaking the boost in academic enthusiasm seen among students in the program. Mckenzie says that she is already ahead of her U.S. history class. Ronnie has found that he’s way ahead on his research skills and knowledge of multimedia tools. Hannah says that she’s getting straight A’s. She adds, “That knowledge I got from the program made me want to be an archeologist when I grow up.”

That is what MIHV does, says Payne. “We use the past to get students to dream about the future.”