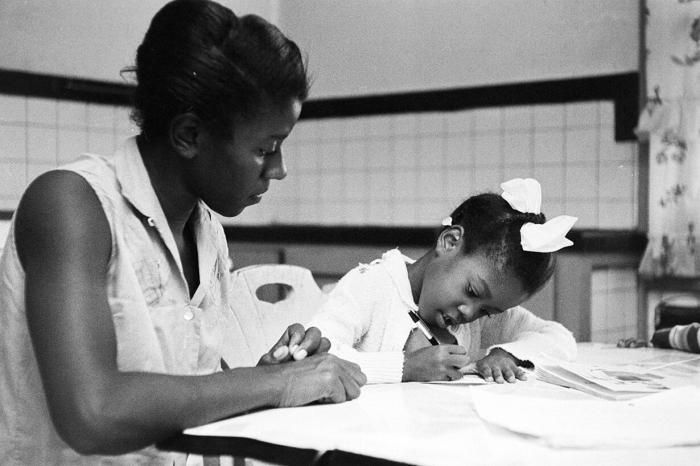

On November 14, 1960, Ruby Bridges walked into the first-grade classroom at William Frantz Elementary School in New Orleans, the first black child to ever attend the school. She had no understanding of the history that led to that moment and no idea that she was making history; she was just a kid going to an all-white school for the first time.

But her attendance was more than what it seemed. It was the culmination of a decade of local, state and national legal battles. She was living a moment that had been shaped by nearly a century of post-emancipation struggles in the South.

The history of slavery—which ended in the United States over 150 years ago—is still shaping contemporary patterns of school segregation through its influence on our social institutions and our reliance on historical precedent and local tradition. The history itself happened long ago, but its legacy is a contemporary phenomenon because our social realities today are informed by what happened yesterday—including our less flattering moments. So, although people today are not individually responsible for slavery, we are very much responsible for how we respond to that history.

As academic researchers, we use this understanding to guide the questions we ask and attempt to answer. It is what led us to investigate whether counties with stronger attachments to slavery have a higher level of school segregation today. (It is important to consider racial segregation broadly, but this particular study focused on segregation between white and African-American children.) We found out the answer is yes, but not for the reasons you might think. Our research paper, “How the Legacy of Slavery and Racial Composition Shape Public School Enrollment in the American South,” shows that, in places that were historically more dependent on the labor of enslaved people, more white families disinvest from public school systems in favor of private schools. Moreover, this relationship is not a result of economic differences, school quality or even the sheer availability of private schools: White families in these locations are simply more likely to use private schools than in other parts of the country.

New Orleans: A Case Study

In the years following Ruby Bridges’ historic day at William Frantz Elementary and the subsequent desegregation of New Orleans schools, the state rapidly increased per-pupil spending for black students. With funding closer to equal than it had ever been, the racial gaps in school resources decreased, and black educational attainment across Louisiana rose.

This piece of Louisiana’s history illustrates the potential benefits of school desegregation, namely that black students obtain access to higher quality educational resources and, subsequently, succeed at higher rates. But Louisiana schools also reflect contemporary challenges related to school segregation. Despite gains from the 1960s through the 1980s, racial segregation is on the rise now that many school desegregation mandates have been lifted, and black students are once again—according to sociologist Dennis J. Condron and colleagues—at an increasing disadvantage.

The once racially integrated William Frantz Elementary is now Akili Academy of New Orleans, an elementary school that focuses on early college preparation. Despite its state-of-the-art veneer, there is one startling feature of this school’s trajectory. Far from its history as, first, an all-white school, then a desegregated school where white and black children learned side-by-side, it is now 98 percent black, reflecting the same resegregation trends seen in countless other schools across the region and country.

The Realities of Desegregation

Based on enrollment data from the National Center for Education Statistics, if black and white students were evenly distributed across public schools nationally, each student would attend a school that was about 50 percent white and 15 percent black. But researchers observe a startlingly different reality. According to a report published by the Civil Rights Project, in 2011 the average black student attended a school that was 48.8 percent black and 27.6 percent white. On the flip side, the average white student attended a school that was 72.5 percent white and only 8.3 percent black.

The separation of black students from majority-white schools (and the resources that accompany them) has real consequences for the lives of black students. In more racially mixed school districts, black students perform better in math and reading than their counterparts in school districts where black students are more isolated. Moreover, some majority-black districts lack the resources necessary to offer a complete schedule of core academic courses. The U.S. Department of Education Office for Civil Rights found, for example, that about 25 percent of schools with “the highest percentage of black and Latino students” do not offer Algebra II, and about a third of these schools do not offer chemistry. Absent these courses, the ability of students to attend college—let alone succeed—is stunted.

Desegregation vs. Integration

These unfortunate statistics raise challenging questions. What is the difference between desegregation, which might be a superficial change in student demographics, versus sincere and internally motivated integration? Did the South ever achieve true integration through federal orders, and can this approach be more productive in the future? Asking these questions will position us as researchers and educators to reduce the negative consequences associated with segregation, but these efforts must be informed by history.

After Reconstruction, Southern states and municipalities legally sanctioned a dual public school system where white students would attend one set of public schools and black students would attend an inferior set of schools. During the Jim Crow era, the United States was under de jure segregation, meaning that the law supported the separation of black and white students. But after Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka (1954) and subsequent rulings demanded the immediate desegregation of schools, the legal formality of the dual school system collapsed. This means that more recent forms of school segregation are supported by alternative mechanisms that are more difficult to regulate through law: de facto segregation, or segregation that happens as a matter of fact.

What’s one mechanism that has supported de facto segregation? Private schools. As black students began to enter white public schools across the South, a vast network of private schools appeared, seemingly overnight, to offer outlets for white families seeking to escape the results of school desegregation. This private school system created a new type of dual school system, with most black students attending public schools and most white students attending private schools. Schools were technically desegregated, but far from integrated—and far from equal.

How Did We Get Here Again?

The type of school segregation we study is founded on the physical separation of black and white students. Research suggests that one of the most relevant variables contributing to school segregation is white families transferring their children from majority-black public schools. Charles Clotfelter, a professor of public policy studies at Duke University, demonstrates the importance of “white flight” through analyses linking schools’ racial compositions to the departure of white students. His work suggests that the tipping point for withdrawing white students from desegregated public schools is a black student population of about 50-55 percent. But why?

The work of Kimberly Goyette, a professor of sociology at Temple University, and her colleagues suggests one explanation relates to perceptions of school quality. They found that white people tend to perceive an inverse relationship between the quality of a school and the number of black students who attend it. Although concern about school quality is often given as the reason for leaving a school or moving to a new district, this explanation may be coded language masking a racialized motive. In a study of school choices made by parents, Amanda Bancroft, a graduate student at Rice University, finds that “high-status parents” (parents of high socio-economic class located in affluent neighborhoods) often relied on informal suggestions about what constitutes a “good” school and did not draw on the publicly available school accountability data that helps quantify school quality.

Although people today are not individually responsible for slavery, we are very much responsible for how we respond to that history.

Other research recently collected in Choosing Homes, Choosing Schools, edited by Goyette and Annette Lareau, further examines how passively or anecdotally acquired knowledge about school quality shapes families’ actions, including residential decisions, which can also serve to maintain school segregation. Residential segregation and the factors driving residential decisions are important for understanding school segregation. But school segregation can happen without residential separation, particularly in the South where there are fewer available districts to which white families can move to avoid majority-black schools. Instead, families may seek to use private schools, which may explain why, according to Clotfelter, the proportion of white students using private schools in the South since the 1960s has risen while their usage has declined in other regions.

The results of “How the Legacy of Slavery and Racial Composition Shape Public School Enrollment in the American South” show that the old idioms are wrong. The past is not the past. It continues to live with us and shape social reality. The racial history of counties found in the Deep South—Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, South Carolina and Texas—are unique and have shaped a system of de facto school segregation that cannot be explained by any other characteristics of these counties. This research highlights the importance of history in shaping contemporary school segregation and suggests that how white people respond to race today is connected to ideas that persisted under slavery. Educational stakeholders must also use knowledge of the past to shape perceptions of the present and use those mutually enforcing understandings to positively influence the future.

Looking to the Past

Part of what is so pernicious about history is that people forget to talk about it. Our research provides the mental tools for thinking about how history is connected to contemporary education, but we also hope to motivate educators to incorporate history into the classroom in fresh, innovative ways. Here are a couple of ideas to get you and your students talking.

James Loewen has written a helpful and accessible book that captures the ways in which history is both complex and socially constructed: Lies My Teacher Told Me: Everything Your American History Textbook Got Wrong.

Field trips that allow students to interact with their own local history can be particularly enlightening. (See “Hit the Road” and “Doing History in Buncombe County” for ideas about how to leverage local history.)

Ask students to evaluate their textbooks, school/classroom environment and celebration calendar to see which historical figures are reflected and which identities they represent. Then have them inventory whose history is present in their school experiences and whose is overlooked.

0 COMMENTS