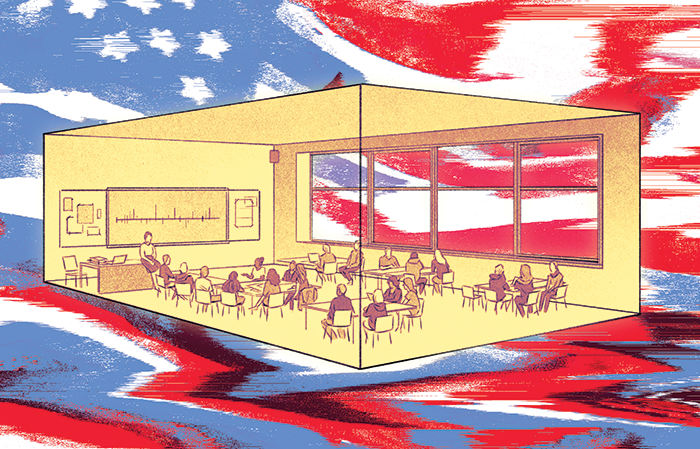

Q: I’m a high school teacher dreading the spring when the political process will heat up. I’m concerned about how it will impact my students and our school climate. What should I do to prepare?

One thing to remember is that your students will most likely have concerns about this as well. Involve them in the process by asking about those concerns. Together, discuss how you might address partisanship when it manifests in your school or classroom. You can collaborate to devise a plan that will create an inclusive and supportive community. Consider how you’ll hold yourselves accountable by checking in regularly to see how everything is going.

Another way to combat the effects of political polarization is to explicitly teach about it. This can be done in a way that is not partisan. Start by helping students define what polarization is and what contributes to it. It’s important for students to better understand how competing ideologies drive our political parties as they try to answer important questions like, “What is a good society, and how should we get it?” Finally, remember—and remind your students—that elections are an opportunity to help shape the future we want. Encourage students to consider their own ideas about what makes a good society and how we can achieve it. Doing so will help them recognize the power they hold as contributing members of a diverse democracy. And the more engaged and informed students are about the issues that affect their lives, the harder it will be for them to fall back on partisan talking points.

I’m a new teacher at an elementary school that does Pioneer Day, part of which requires students to dress up. I have concerns about the day itself and especially about students being asked to dress up. What should I do?

Theme days, even those directly related to curriculum, can be problematic. When enacting historical narratives, it’s important to ask: “Whose story is being told?” Since history curricula often sideline or silence some experiences and perspectives, some students can feel left out. They might even be placed in a traumatic position, given the historical treatment of people of color. These activities also run the risk of cultural appropriation, since historical dress might be viewed as costume or as dress-up time by students.

You are probably not the only one at your school who sees a problem. We suggest clearly explaining your concerns to your colleagues and proposing changes. Consider how this event could tell a more complete story, become more inclusive, provide more critical engagement with the content and also meet your educational objectives.

Some possible changes might be having students research your town or community and then present their findings. Or they could take a virtual field trip to learn more about life during this time, especially learning how different groups of people were living. You and your team should invite students and their families to participate in the planning of this day so that all voices can be heard and an equitable activity can be enjoyed by all.

0 COMMENTS