When you discuss the history of voting rights in the United States, you can’t avoid talking about the distribution of power—and how that power has been abused in deliberate and obvious ways, both historically and into the present day. One way those in power consolidate power is through voter suppression. Another is through gerrymandering.

Editor’s Note: This article was first published in the fall of 2018, before the midterm elections.

What’s gerrymandering? We’re glad you asked!

Gerrymandering is the drawing of political boundaries with the intent to ensure that one party has a clear advantage over its opposition in elections. Gerrymandering in all of its forms is based largely on assumptions about how people will vote, and it’s motivated by a desire to stay in power and to ensure predictability in election results.

One reason educators may avoid tackling discussions of gerrymandering in their classes is that they worry these discussions can quickly turn partisan. While gerrymandering is, by nature, a political practice, it’s fairly easy to keep your discussion of the practice nonpartisan.

You can start by teaching students what gerrymandering is. The process takes different forms to serve different—but often related—purposes.

Bipartisan Gerrymandering

Unlike the partisan gerrymanders that students may already know about, in bipartisan gerrymandering, the two parties come to an agreement on how to draw district lines to protect those already in office.

While your students might think this doesn’t sound too bad, you can push them to consider how this is a problem. Bipartisan gerrymandering can block new candidates and their ideas from being given a fair shot—leading to a stagnation of policies and ideas. It prevents emerging constituencies from having their ideas heard and stops them from electing candidates who might share and fight for their views. The following example can help students understand how bipartisan gerrymandering works.

In one state, there are seven congressional districts. Six districts are represented by officials from party A; one district is represented by an official from party B. That district has been gerrymandered to include two of the state’s larger cities (and their more liberal voters)—even though these cities are located almost two hours away from each other. Unlike the rest of the state, whose residents live in smaller towns or rural areas and often vote for party A, this district has voted overwhelmingly for party B in general elections since 2000 and has been represented by party B representatives for 25 years.

In this example of bipartisan gerrymandering, large populations of liberal voters are grouped together to consolidate their votes. Both parties expect party B to win the gerrymandered district because, historically, liberal voters almost always vote for party B there. This allows party B to know they’ll have a representative, and it allows party A to focus their energy on the other six districts of the state, where they maintain their power—and where there are no surprises on election days.

Racial Gerrymandering

Unlike bipartisan gerrymandering, which is generally reached through agreement between the major parties, racial gerrymandering is often used so that one party can maintain control without worrying about challenges from the other. This type of gerrymandering manipulates the voting power of certain demographics (especially racial groups) in ways that either confine that particular block to certain areas or dilute the concentration of minority populations by integrating them into multiple majority districts. When explaining this to students, you might offer an example of what racial gerrymandering looks like.

Ask them to consider a city (City A) with a majority-black population, located near three other cities whose populations are mostly white. When legislative districts are drawn, City A is divided up, and its residents are sent to vote in three different districts. Each of those districts also includes one of the neighboring, majority-white, cities. While City A’s residents live in a city that’s mostly black, they vote in districts that are mostly white. Unsurprisingly, the officials who represent citizens of City A are almost always from one of the neighboring, mostly white cities. When this happens, the interests of City A’s black population might not get as much attention as they would if that population were kept together during the drawing of the districts.

Looking at Real-life Examples

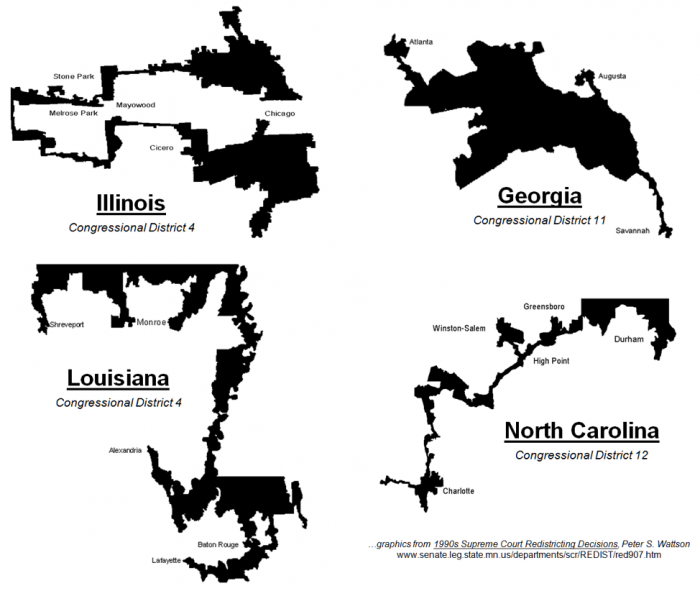

Your students may wonder what gerrymandered districts look like. Unfortunately, there are plenty of examples of gerrymandering in the past and present.

To help them understand how districts are drawn, you might share some basic information about legislative redistricting. You can let them know that districts are redrawn every 10 years, based on information collected by the United States census—our next redistricting will take place in 2022.

You can also explain that districts are drawn at the state level, and you can let students know who draws the districts in your state.

Finally, you can ask them to consider some of the information required by law for drawing legislative districts. Here are some key criteria:

Population equity: Each district should have close to the same number of people.

Contiguity: A district should not be divided into multiple pieces except only in limited circumstances.

Respect for existing political subdivisions: Towns, neighborhoods, municipal areas, etc. should be kept intact when district lines are drawn.

With these basic rules for how districts should be and shouldn’t be drawn, ask your students to test these rules against examples of some legislative districts. Have them discuss whether these district lines make sense. Given the basic guidelines for drawing boundaries, why would these districts be drawn in this manner?

Voting is a critical piece of our democracy. It’s a sacred right that touches government on every level. It also touches each of our lives and the lives of our students. Most immediately, voting determines whether our schools—and our students—receive the resources they need to succeed.

Throughout history, voting has served as an avenue for necessary change in this nation. It has also served as one of the most effective ways for people in power to hinder progress and resist change by maintaining the status quo. Teaching your students about the importance of the vote and of protecting a fair, free vote not only reinforces their understanding of justice and equality; it also protects the diverse democracy that our students will one day lead.

Smith is a program associate for Teaching Tolerance.

0 COMMENTS