Editor’s note: This article was originally published in March 2020.

March has been a rough month. In fact, this whole year, so far, has been unkind. We hope, no matter your school community’s strategy for continued learning, that you’re prioritizing students’ well-being over assignments during this time. But we also want to continue offering resources that might serve as alternatives or lighter lifts as we all figure out how to teach and learn in this space.

As we wrap up Women’s History Month, we want to emphasize that this history doesn’t have to be relegated to March. It should be discussed year-round. We also encourage educators to capture the fullness of women’s roles in shaping United States history. Rather than relying on stories about the same barrier breakers, dig a little deeper to acknowledge and celebrate women who were more likely to be erased or silenced.

While Women’s History Month serves as a way to elevate women’s roles in shaping American life, not all women’s stories are included in textbooks and mainstream narratives. Educators must teach students to interrogate how historical narratives are crafted and framed—to seek truth and tell complete stories. In an interview with Vice about her book, The World Made by Women: A History of Women From the Apple to the Pill, author Amanda Foreman put it this way: “The tools of oppression begin with the stories we tell ourselves about ourselves, and that’s why you have to set the record straight.”

Womanhood can’t be narrowly defined because women are not a monolith—there is more than one way to be a woman. Students, with their diverse and intersecting identities, already recognize this. During women’s history month and throughout the year, we can share lessons and discussions that acknowledge people who look like them or have similar experiences. Doing so will help students not only push back and correct incomplete historical narratives but also identify gaps they find as they work toward finding those truths. If students can’t see their identity reflected in history books, it’s imperative that they understand it’s the recounting of history that is wrong—not their identity.

Part of setting the record straight about women’s history is acknowledging the common belief that all women conform to certain norms, behaviors, roles and aesthetics. Women who step outside of those boundaries are often ostracized or omitted from history books and other records.

But too often, narratives we hear during Women’s History Month don’t do enough to address this. Stories often don’t consider women’s gender expression, sexual orientation, race, ethnicity and ability as significant parts of their life’s story. Instead, observations in March tend to speak of women’s achievements only in the context of overcoming gender barriers, discrimination and violence.

It certainly is important to teach how women have resisted oppressive systems while being excluded from power. But it’s also imperative to include the many ways they show up as their authentic selves as they work to dismantle systems of oppression.

Teach Context Behind Firsts

We often don’t learn about women who’ve contributed significantly to science, human rights movements and the arts until movies are made about them. It’s important that their legacies go beyond exceptionalism and the stories of women who were the first to break barriers in their field. It’s helpful to name systems of oppression to provide context about their stories. Naming oppressive systems is one way to help students recognize gaps in the retelling of history. It also illuminates why certain women’s stories weren’t deemed as valuable.

For example, students could study why Black women scientists such as Marie Maynard Daly, Katherine Johnson and Mae C. Jemison were among the first Black women to excel in their field as late as the 20th century. They can recognize that while these women overcame both racial and gender barriers, the same systems that made it more difficult for them are still in place. Students can look to their own experience or to recent studies to consider how young women, and particularly young Black women, are supported or discouraged from courses and careers in STEM.

Even when women’s lives are highlighted during Women’s History Month, it’s worth thinking about what kinds of stories get told. Recovering hidden history can be more than just teaching new names. For example, students may be familiar with Harriet Tubman’s work to free enslaved people and spy on Confederate sources, but the fact that she led the Combahee Ferry Raid—a successful military operation—is rarely emphasized in Women’s History Month narratives.

Throughout history, women exuded strength and courage while ignoring gender norms, like those who disguised themselves as men to fight in the Civil War. You can teach students to recognize hidden histories by teaching about the experiences women had during the Civil War, such as Tubman and Frances Clayton, who served in the Union Army alongside her husband.

Elevate Hidden Stories

Women who expressed their authentic identities are also largely hidden from popular narratives. Another way women historically challenged patriarchal nuclear family structures was through the concept of Boston marriages—an arrangement in the 19th century where adult women established households together, for romantic love or a system of support. They also created networks for professional women and advocated women’s rights.

In our Queer America podcast, “Romantic Friendships: Boston Marriages (Part 2),” historian Susan Freeman explains, “Coupled women in so-called Boston marriages belong to a generation referred to as New Women, or they were one of the generations of New Women, pioneering opportunities for women in higher education and professions and in public life.”

It’s important students understand that this happened mostly in the Northeast, and among middle class or wealthy white women. Their privilege provided access to education and financial independence, making it easier to exercise autonomy. Highlighting this privilege helps students to see how some people within an already marginalized group can hold some power while others experience added layers of oppression.

The influence of queer women during the Harlem Renaissance can show a different way women have created space to live authentically. Their work to carve out space for the Black LGBTQ community in Harlem laid the blueprint for other LGBTQ communities of all races, genders and backgrounds across the country.

In the article “Black Face, Queer Space: The Influence of Black Lesbian & Transgender Blues Women of the Harlem Renaissance on Emerging Queer Communities,” Emma Chen writes, “During the Harlem Renaissance, not only did black culture and arts flourish, but lesbian/transgender black women were also able to create opportunities for freedom of expression and visibility which established the framework for an emerging black LGBTQ+ community and constituted an opening for recognition by some members within the straight community.”

Citing Blues Legacies and Feminism, Chen goes on to say that “blues woman openly challenged the gender politics implicit in traditional cultural representations of marriage and heterosexual love.”

Address Appropriation

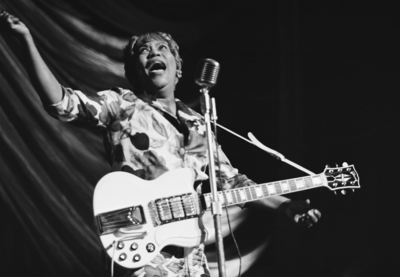

One last figure to learn about and later introduce to students is Rosetta Tharpe, the godmother of rock-and-roll. In the late 1930s, before Little Richard, Chuck Berry or Elvis Pressley, Tharpe, a Black, openly queer woman, introduced a distinct style of music that blended gospel, blues and jazz and included electrifying guitar playing. It was rare at the time for women to play the guitar, let alone in the thrilling way in which Tharpe played.

While many contemporary rock-and-roll stars laud Tharpe as an inspiration for their music, students may question why her story was largely absent from historical accounts of American music history for several decades. For the latter part of the 20th century and going into the 21st century, many Americans had not yet grasped that rock and roll was not the creation of white men, but Black artists like Tharpe. Her rejection of gender norms, her sexuality and race all played a part in being relegated to the history margins. She wasn’t inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame until 2018.

The list of women who don’t fit neatly in a patriarchal, heterosexual, feminine narrative is long. Their contributions to their communities and our country as a whole are paramount. And these achievements certainly aren’t limited to women we find in history. Look in your community or encourage your students to look into their families to find remarkable, inspirational women.

We hope you’ll take some time to consider how we celebrate and elevate all women who show up in different ways. As educators, you can inspire your students to see more women who were just as impactful as their male counterparts—not just during a commemorative month, but year-round.

0 COMMENTS