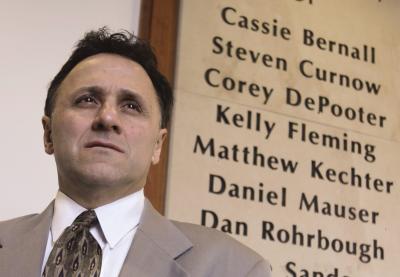

In the immediate aftermath of the Columbine school shootings, Principal Frank DeAngelis felt, in his own words, "the weight of the world on my shoulders." Five years later, he still struggles for answers — and still loves his job. Teaching Tolerance Research Fellow Emily Vickery spent nine days at Columbine leading up to the five-year memorial of the shootings. Here are excerpts of her interview with DeAngelis, a man whose face and voice have become intertwined with the story of Columbine.

Tell me about the sense of community, for Columbine, in those early days.

I think what everyone was feeling at that point is just reconnecting. There was a special bond that developed as a result of the tragedy. I think that connection was good from the standpoint that it allowed us to get through it; we worked as a group, as a family. And I stress the importance of family.

But on the other side ... it created some problems with ... spouses and significant others, because I think the attitudes so many of us took on — even though we greatly appreciated the sympathy and the empathy that was being shown by so many — was the attitude, You have no idea what I'm going through. You were not there.

What about the students?

It was a Thursday ... probably later in the afternoon, and all of the students were going to come together. There were some counselors that were working with the kids. ... I had no intention of talking to the kids at that point, but some of the teachers wanted to go over and see how the kids were doing.

And the counselor said, You need to get over there. They really need someone to talk to.

And I went over there. And it was good for me, and it was good for the kids and good for the staff members.

There were some tears. That was one of the things that really helped them, because they saw me cry, and I think it gave them permission to cry. And they started the chant, "We are Columbine."

Talk about the media, how they told — and continue to tell — the story of Columbine.

I remember Friday morning [the week of the tragedy], meeting with all of the media, Good Morning America, The Today Show, starting at 5:30.

It was snowing outside, and it was just cold as can be. And we thought we were going to be inside, and we were not. And I can remember sitting with the lights flashing on me and looking over at the building.

It was just — it was, like, surreal to see the snow falling. It was an eerie feeling.

I realized that Friday that it was going to be difficult, because there were so many stories out there. And I'm saying, This cannot be our school. I've been here 20-some years. This is not the school I know and love.

And it got to the point, I think people that were here started questioning, God, did I miss something? You start reading all of these things, and you're wondering, What happened? But bottom line is I knew in my heart that we had done everything we could.

Teachers were fantastic. Students were fantastic. I remember stating — people asked me — I said, It will all come out. It will come out. And I know in my heart that we're good people. And it's a tragedy that, unfortunately, happened. And I wish we had answers. Five years later, we still don't have answers.

What got you through that, through those early days?

Number one is the staff and the students were very supportive. Students gave me a notebook and just wrote some very neat things in there. And I would sit down and read it whenever I needed positive things.

And the other thing, too: I'm a very faithful person. I put my life in the hands of my faith and God. When I came to the realization that my judge is not on the face of this earth, I was able to move forward. I was able to live with myself, and I was able to look in the mirror and say, There's going to be a lot of people that try to judge me, but my judgment is not on the face of this earth. It will be in the hereafter.

Work In Progress

Clement Park, adjacent to Columbine High School, has become an impromptu place of mourning and prayer as people try to absorb the shocking events of April 20, 1999.

The fitting spot will become the permanent home of the Columbine Memorial — a place to honor those killed and injured in the shooting, and a place to recognize the healing of all those affected.

Plans for the memorial began five years ago. Since then, 1999 high school graduates, parents of the victims, school faculty, public officials and community leaders have coordinated planning and raising funds for the project.

The memorial's design is based on the results of committee workshops, 3,500 community-member surveys and the feedback of the victims' families, as well as input from families of those injured in the shootings.

Roughly half the size of a football field, the memorial's atmosphere will be peaceful and meditative. The "Never Forgotten" Columbine ribbon, which has come to embody community unity and strength, is woven into pavement and landscaping designs.

According to Bob Easton, chairman of the Columbine Memorial Committee, fundraising, attaining unanimous design approval from the victims' families and dealing with declining interest due to the passage of time have been the project's main stumbling blocks.

However, Easton said, "The process itself has been rewarding because of the relationships that have been nurtured with families and community members."

Project costs are estimated at $3 million, with $2.5 million allotted for construction and $500,000 designated as a maintenance endowment.

The local recreation district will oversee memorial maintenance, and plans are in place to establish a volunteer group to help with the upkeep.

In July, President Clinton pledged his continued support helping fundraising efforts. To date, about $1 million has been raised, which is roughly 38% of the needed monies. Construction will begin when 80% of the funding is in place, according to Easton.

"The final reward will be the completion of the project," Easton said. "The committee is dedicated to whatever is necessary to build the memorial."

What about that first graduating class, the Columbine class of 1999?

I can remember the seniors' last day. I just stood in the middle of the hallway or in the middle of the cafeteria just crying because I just said, These kids were cheated so much.

I mean, they lost their friends. They lost their innocence. And they lost their school. I just thought, It's so unfortunate that these students had to go through that.

We had students who came across the stage [at Fiddler's Green Amphitheatre, where Columbine students held their graduation] — Lisa Kreutz, Jeanna Parks, Valerie Schnurr — who were shot a month earlier and released from the hospital in wheelchairs to come across and get their diploma. That was courage: those kids making it.

I can remember Dawn Anna and Bruce Beck coming up — Laura Townsend's [mother and stepfather] coming up. Because she would have been one of the valedictorians, and that was very difficult presenting that plaque.

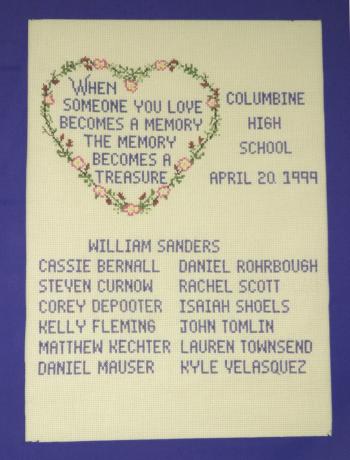

And each year for the next three following, we would do a moment of silence and read the names of the students who had passed away, who had been murdered, that should have graduated. It was very tough, very emotional.

So you were at Chatfield High School for the end of the 1999 school year, but that fall, you reopened Columbine. Tell me about that.

Things I never had to anticipate doing prior were now in my thoughts every day. Meeting with mental health workers to choose the color of paint that would be soothing to students.

I can remember spending hours coming up with the sound for our fire alarm system because many of the students that were returning were trapped in this building, and we could not have anything that was similar to what had occurred or what they had heard back on April 20. We did not want to serve food that would remind the students of what they had eaten that day.

Things that you don't even anticipate, such as telling faculty members as far as curriculum, things that they could or could not teach. You needed to be sensible. I mean not showing videos in which there was gunfire. And not having balloons in school because if they popped it would re-traumatize the kids.

There was a theme at that time, "Take Back Columbine." Where did that come from?

There was a time at Chatfield, and the students came in and they said, Mr. D, don't let them take our school. If you allow them to take our school and we're not allowed to go back in there, then the two murderers won. So I realized we needed to come back into this building. And that was the theme.

I remember parents formed a sort of protective cordon around the students that day, welcoming them back to the school and protecting them from the media. What else happened?

We had a big rally here in the student lot. I can remember the person leading the staff and the students in the building was Patrick Ireland [the student who hoisted himself down to safety after he had been shot]. So that was not only symbolic, gosh, it was just so encouraging.

The one regret I have about that day — thinking back to it now — I don't know why I didn't do it. You do things, and you don't know why. But one of the things we did not mention that first day back is the 13 who were murdered.

The families of the murdered were very hurt, and I felt bad because I had hurt them. I mean, I struggled with that, until I called each parent to apologize and stated that we would make it up to them; their children would never be forgotten.

Have they been forgotten?

(I hope) each time the sun rises or a flower blooms, (we) think about our children and think about life, because they represented life, not death. So that's what it's about. So you build upon that.

... I'm hoping, and I truly believe, that the world is a better place than it was five years ago.

I think every school in this nation — every school in this world — looks at things differently as a result of the tragedy of Columbine. I think parents look at things differently. I think law enforcement agencies are looking at things differently than prior to the 20th.

Very similar to what happened on September 11th, people are looking at things differently. They are more vigilant. And I think it's so unfortunate people had to lose their lives in order for this to occur.

How do you look at Columbine differently, now?

I think — you learn — you're hoping that we're a better school, we're a stronger school. Our students are more compassionate, more understanding. You're hoping that good comes out of the evil that occurred.

People are more tolerant of one another. You respect one another. They respect life; they respect property.

Are we there? I think we're in a better place than what we were, most definitely, back in April of '99 or before April of '99. I think we're a stronger community. I think the tragedy brought us together. I think we're moving ahead.

And I think what's so frustrating is you keep moving ahead, and then all of a sudden you run into a bump in the road that really alters your plan.

What's an example of a bump?

Trying to make everyone happy. I can't. You just — I have to do what I feel is best for Columbine High School. And a lot of times people disagree. ... You may not agree, you may agree, but the thing you need to do is respect where people are, because there are people in different places.

What place are you in?

I'm struggling right now, because I'm having some feelings, emotionally and mentally and physically, that I haven't had for a few years. I'm going to start talking to my counselor again.

And what is happening to me is because I'm in the planning stages for the fifth year [memorial], having flashbacks to what happened that year after. The media is back; I mean, more requests are coming in. ... It's bringing out some emotions that I haven't felt in a while talking about Columbine and what happened and where people are.

I remember a faculty meeting where I told people what I was feeling. And it was my way of stating, I don't know if anyone else out there is feeling this, but I have to go back to my counselor, because I got scared.

I said, My blood pressure is up. My heart is racing. And I finally realized, after watching those videotapes that were on TV, after reading the news, that I was re-traumatized.

And I gave people permission to say, Gosh, it's not just me. There are others feeling that. Because I think a lot of times you're afraid to say, Is something wrong with me?

What other emotions arise at the five-year mark?

(At) the one-year anniversary, (the stories) were about the bullying and the finger-pointing. But now I think more people — what I've noticed at five years is they are approaching it differently: What have you learned? Where are you five years later?

It's a much different feel than that first year. ... How did your community make it? Why are you still there?

Why are you still here? Did you ever consider leaving Columbine during these five years?

(Some people are) shocked I am still here. I think everybody would have felt I would have lasted one year. And they said, Maybe he'll carry out the three-year promise that he made to those kids.

Three-year promise?

I told those kids right after the tragedy — I said, We're in this together. We're all family. And I'll make you this promise, that if you're here, I'll be here with you.

The summer prior to the class of 2002 starting school, ... I knew I had to make a decision whether or not I was going to leave Columbine and go somewhere else. I struggled with that, because I loved this place. And I still love this place.

It was one summer night or day that I was walking my dog, and I realized, I'm definitely going to be there to see the class for 2002, because I'm going to stay until I decide it's time to go.

I think what ends up happening is we're so close to the situation that until you talk to someone from the outside, you don't realize what we've been able to overcome. It's nice to hear outsiders come in and say, Do you realize how special a place Columbine is?

What happens next for Columbine?

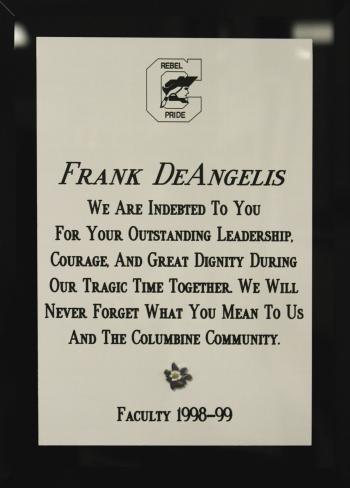

I look forward to finishing my career at Columbine High School. The members of the school community have provided the strength and inspiration that I so badly needed.

It's the message we have been repeating: a time to remember, a time to hope. We will never forget the people who lost their lives, and their memories will provide the hope for a bright future. We will continue to heal.

We hope that many lessons have been learned and such a tragedy will never occur again.

0 COMMENTS