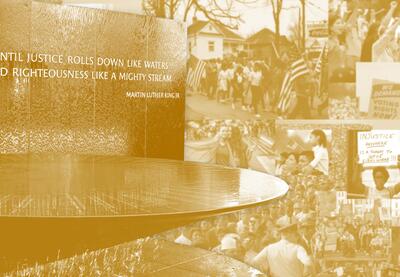

The history of the United States involves, at its foundation, the struggle to expand democracy to people who have been denied even the most basic rights and liberties. Centering the perspective of white cisgender men, a white supremacist social structure has been the dominant narrative, maintaining its power through violence and intentional barriers to freedom and justice. That oppression, however, has never gone unchallenged. The fight for justice has deep roots in our shared history and is dynamic, embracing current intersectional struggles. This connection between past and present and among diverse movements is keenly reflected in the Civil Rights Memorial Center (CRMC), located in downtown Montgomery, Alabama.

The Civil Rights Memorial Center (CRMC)

The Center opened in 2005 to honor the people who died fighting for civil rights and justice. Today, visitors walking through the Center engage with a learning space that is much more than a repository for civil rights movement history and its heroes. The Center now highlights current intersecting movements, with four galleries that serve to spotlight the Southern Poverty Law Center’s (SPLC) work in support of those movements. The galleries include: the Orientation Theater, the Wall of Justice, the Martyr Room and a hallway that focuses on today’s activists and the work that continues in the march for justice.

“Before we did the renovations, people would come in thinking, ‘Okay, it’s a civil rights museum,’” recounts CRMC Director Tafeni English. “Then there were other people who came in and they thought that this was all about the deep dive of the work that SPLC was doing. We can give them both.”

Voting rights, Black Lives Matter, the fight for inclusive schools, disability rights, LGBTQ+ rights and women’s rights are among the intersecting movements highlighted at the museum. In contrast to the reverent atmosphere in the Martyr Room, the gallery highlighting current movements toward justice reflects a colorful and vibrant energy to evoke hope and inspire action. In that hallway dedicated to more current activists, the names of individuals from recent history—including Islan Nettles, Khalid Jabara, Richard Collins III and Heather Heyer—killed by white supremacists join the names of those slain more than 50 years ago.

Drawing the connections between past and present movements opens up space to discuss the communities and people who aren’t always acknowledged in history textbooks or in public discourse. For example, the roles of women, children and the LGBTQ+ community have largely been left out of narratives of the civil rights movement, or viewed as secondary, even though the movement could not have happened without their immense contributions and sacrifices.

“Ella Baker was saying give people light and they will find a way. But … people [must] … understand that that light will look different for everyone. And your comfort level may be writing a letter or signing a petition, where somebody else’s comfort level may be organizing and leading a protest. Somebody else’s radical may be ‘I’m running for office.’” —Tafeni English

English explains that the Center aims to update the museum’s content to keep up with what’s happening in the world. It’s important to go beyond thematic months and events, such as Women’s History Month or Martin Luther King Jr. Day. And while some museums are becoming more mindful of explicitly sharing an honest, inclusive history, some struggle to keep up with current events. “It’s important for museums to update more frequently than you have seen in the past,” English says. “Most museums keep their exhibits 25, 30 years. Some never change their exhibits. But with us, because we want to be a part of the museums who are also part of the community, and central to the community, we want people to come here and walk away with things that are happening currently in the community that they can get involved in.”

Inspiring Learning and Making Connections

The Center staff welcome visitors from across the country, including Alabama fourth graders—whose visit to the exterior Memorial is part of the state’s history curriculum. The Center is vital for young visitors as it takes them on a journey to help connect the past with the present and therefore has the potential to keep the movement-building momentum going.

Visiting groups have an opportunity to tell the Center staff what they already know about this history, and what they’d like to learn more about. Student visitors are tasked with examining the plaques in the Martyr Room that provide details about the life of a person who died in the movement. They are asked to pay special attention to those they’ve never read about in history books. Educators are encouraged to have honest conversations with their students before, during and after visits, and are also urged to anticipate emotional reactions that could arise from the experience.

The Center offers a curriculum to support educators and community advocates. A guide for high school and college students contains lessons, discussion questions and the exploration of age-appropriate key concepts. For younger students, a children’s activity book is available.

All About the People

Outside the Center, there are historical sites and markers in every direction. Some detail the fight for civil rights or the city of Montgomery’s role in slavery. And just around the corner from the Center stands the church where Dr. King led a congregation and where members continue to worship to this day. English says it’s crucial that the Center remains grounded in the local community and listens to those who are affected by the issues they uplift. It’s all about the people. The Center is charged with not only creating a space for honest history education, but also presenting humanizing portraits of the people who fought for social justice.

The Martyr Room overlooks the Memorial outside—a round black granite table that pays homage to 40 men, women and children who were murdered in the struggle for civil rights. At an interactive table in the room, by going beyond the details of the traumatizing deaths of the individuals honored there, visitors can explore specifics about each person’s life. English explains that, with the help of family members of those honored at the Center, these small details shed light on how they lived and the things they enjoyed. The Center’s staff also explain to visitors how, long after the murder of a loved one, white supremacy impacted every facet of life for family members. And that provides an opening to connect to highly publicized deaths today. “I don’t think people think about the aftermath of what families are left to struggle and deal with,” English shares. “Not only are they having to grieve, but they’re also—each and every time—having to defend their loved ones in their death.”

Visitors to the Center can also gain an understanding of the history of police violence against Black people in the United States. Roman Ducksworth Jr., a military police officer and a father of six, is one person highlighted at the Center. Ducksworth was traveling from where he was stationed in Maryland to his home in Mississippi when he was murdered by law enforcement in 1962. While people may not recognize his name—as Ducksworth represents the countless number of largely unreported victims of white supremacist violence—they can make connections to police violence against Black people today. “So, it opens up this conversation about how the fear of law enforcement and overpolicing is nothing new,” English explains. “That was not something that came out of the Black Lives Matter movement. It didn’t start with Ferguson.”

Stepping Into Our Roles

The effects of white supremacy on daily life can feel overwhelming, and for those committed to social justice, the inevitable pushback to progress can be deflating. But feeling overwhelmed can paralyze people who would otherwise be engaged in the movement for a just and inclusive society.

In the short CRMC video, “Apathy is Not an Option,” activists note that it’s imperative to remember there have been social justice victories along the way. However, the work is not over. The video emphasizes that there will always be a liberatory movement as long as the world is unjust, and it explains that everyone has a role to play in making positive change. We are living history now, and we can shape it. People just have to tap into their individual strengths and passions. And that perspective has made large movements work in the past. Individuals offered support where they could, from providing shelter for on-the-ground activists and creating art, to organizing marches and boycotts. After the video, there’s an opportunity for visitors to dive deeply into the subject matter with staff.

“If we present [the challenges] in this big grand scope, more than likely they leave feeling overwhelmed, and they feel helpless, and they don’t know what they can do,” English explains. “Ella Baker was saying give people light and they will find a way. But … people [must] … understand that that light will look different for everyone. And your comfort level may be writing a letter or signing a petition, where somebody else’s comfort level may be organizing and leading a protest,” English adds. “Somebody else’s radical may be ‘I’m running for office.’”

Scaling in from the big picture helps people realize their power. “What I want people to leave with is that [it’s] not just organizations like SPLC or ACLU or the EJIs,” English says. “We have to return the power back to the people, and for people to realize where that power lies and how they can join hands with us in real ways, to really start shifting the political landscape, specifically in the South.”

The content at the CMRC sheds light on the many ways that white supremacy has killed. In addition to acts of violence, some people succumbed to the stress and strain of poverty. “I think that is something that we have to have deeper discussions about—when we’re talking about healing and the amount of trauma—is that we also have to look at the economic injustices and how that continues to oppress and cause health issues,” English notes.

The work of the Center will continue to include perspectives from current activists and community leaders, including the reality that for every social justice issue we face, there is another that affects or compounds it. That’s why many activists today are prioritizing rest, community care and self-care as essential components in the movement toward social justice. These kinds of motivating messages and the context provided throughout the renovated Center are critical to encourage the continued legacy of individuals—ordinary people—fighting together in community for justice and the greater good.

0 COMMENTS